| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

A daily bite-size selection of top business content. |

| |

| |

| |

Quote: Michael Jensen - “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers”“The interests and incentives of managers and shareholders conflict over such issues as the optimal size of the firm and the payment of cash to shareholders. These conflicts are especially severe in firms with large free cash flows—more cash than profitable investment opportunities.” - Michael Jensen - “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers”This work profoundly shifted our understanding of corporate finance and governance by introducing the concept of free cash flow as a double-edged sword: a sign of a firm’s potential strength, but also a source of internal conflict and inefficiency. Jensen’s insight was to frame the relationship between corporate management (agents) and shareholders (principals) as inherently conflicted, especially when firms generate substantial cash beyond what they can profitably reinvest. In such cases, managers — acting in their own interests — may prefer to expand the firm’s size, prestige, or personal security rather than return excess funds to shareholders. This can lead to overinvestment, value-destroying acquisitions, and inefficiencies that reduce shareholder wealth. Jensen argued that these “agency costs” become most acute when a company holds large free cash flows with limited attractive investment opportunities. Understanding and controlling the use of this surplus cash is, therefore, central to corporate governance, capital structure decisions, and the market for corporate control. He further advanced that mechanisms such as debt financing, share buybacks, and vigilant board oversight were required to align managerial behaviour with shareholder interests and mitigate these costs. Michael C. Jensen – Biography and Authority Michael C. Jensen (born 1939) is an American economist whose work has reshaped the fields of corporate finance, organisational theory, and governance. He is renowned for co-founding agency theory, which examines conflicts between owners and managers, and for developing the “free cash flow hypothesis,” now a core part of the strategic finance playbook. Jensen’s academic career spanned appointments at leading institutions, including Harvard Business School. His early collaboration with William Meckling produced the foundational 1976 paper “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure”, formalising the costs incurred when managers’ interests diverge from those of owners. Subsequent works, especially his 1986 American Economic Review piece on free cash flow, have defined how both scholars and practitioners think about the discipline of management, boardroom priorities, dividend policy, and the rationale behind leveraged buyouts and takeovers. Jensen’s framework links the language of finance with the realities of human behaviour inside organisations, providing both a diagnostic for governance failures and a toolkit for effective capital allocation. His ideas remain integral to the world’s leading advisory, investment, and academic institutions. Related Leading Theorists and Intellectual Development

Strategic Impact These theoretical advances created the intellectual foundation for practical innovations such as leveraged buyouts, more activist board involvement, value-based management, and the design of performance-related pay. Today, the discipline around free cash flow is central to effective capital allocation, risk management, and the broader field of corporate strategy — and remains immediately relevant in an environment where deployment of capital is a defining test of leadership and organisation value.

|

| |

| |

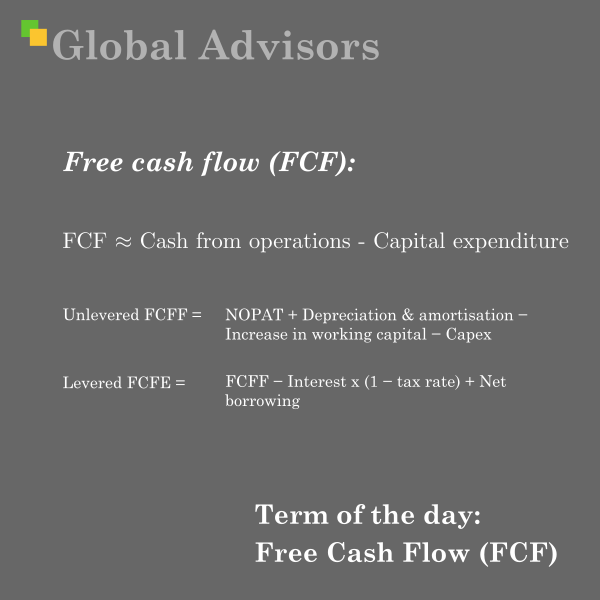

Term: Free Cash Flow (FCF)Definition and purpose

Common formulations

How it is used (strategic and financial)

Drivers and determinants

Common adjustments and measurement issues

Strategic implications and typical responses

Pitfalls and limitations

Practical check list for executives and boards

Recommended quick example

Most closely associated strategy theorist — Michael C. JensenWhy he is the most relevant

Backstory and relationship of his ideas to FCF

Biography — concise professional profile

Further reading (core works)

Concluding strategic note

Free cash flow (FCF) is the cash a company generates from its operations after it has paid the operating expenses and made the investments required to maintain and grow its asset base. It represents cash available to the providers of capital — equity and debt — for distribution, reinvestment, debt repayment or other corporate uses, without impairing the firm’s ongoing operations.

|

| |

| |

Quote: Peter Drucker - Father of modern management“Until a business returns a profit that is greater than its cost of capital, it operates at a loss.” - Peter Drucker - Father of modern managementDrucker argues that a company cannot be considered genuinely profitable unless it covers not only its explicit costs, but also compensates investors for the opportunity cost of their capital. Traditional accounting profits can be misleading: a business could appear successful based on net income, yet, if it fails to generate returns above its cost of capital, it ultimately erodes shareholder value and consumes resources that could be better employed elsewhere. Drucker’s quote lays the philosophical foundation for modern tools such as Economic Value Added (EVA), which explicitly measure whether a company is creating economic profit—returns above all costs, including the cost of capital. This insight pushes leaders to remain vigilant about capital efficiency and value creation, not just superficial profit metrics. About Peter Drucker Peter Ferdinand Drucker (1909–2005) was an Austrian?American management consultant, educator, and author, widely regarded as the “father of modern management”. Drucker’s work spanned nearly seven decades and profoundly influenced how businesses and organisations are led worldwide. He introduced management by objectives, decentralisation, and the “knowledge worker”—concepts that have become central to contemporary management thought. Drucker began his career as a journalist and academic in Europe before moving to the United States in 1937. His landmark study of General Motors, published as Concept of the Corporation, was profoundly influential, as were subsequent works such as The Practice of Management (1954) and Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (1973). Drucker believed business was both a human and a social institution. He advocated strongly for decentralised management, seeing it as critical to both innovation and accountability. Renowned for his intellectual rigour and clear prose, Drucker published 39 books and numerous articles, taught executives and students around the globe, and consulted for major corporations and non?profits throughout his life. He helped shape management education, most notably by establishing advanced executive programmes in the United States and founding the Drucker School of Management at Claremont Graduate University. Drucker’s thinking was always ahead of its time: he predicted the rise of Japan as an economic power, highlighted the critical role of marketing and innovation, and coined the term “knowledge economy” long before it entered common use. His work continues to inform boardroom decisions and management curricula worldwide. Leading Theorists and the Extension of Economic Profit Peter Drucker’s insight regarding the true nature of profit set the stage for later advances in value-based management and the operationalisation of economic profit.

All of these theorists put into action Drucker’s call for a true, economic definition of profit—one that demands a firm not just survive, but actually add value over and above the cost of all capital employed. Summary Drucker’s quote is a challenge: unless a business rewards its capital providers adequately, it is, in economic terms, “operating at a loss.” This principle, codified in frameworks like EVA by leading theorists such as Stewart and Stern, remains foundational to modern strategic management. Drucker’s legacy is the call to measure success not by accounting convention, but by the rigorous, economic reality of genuine value creation.

|

| |

| |

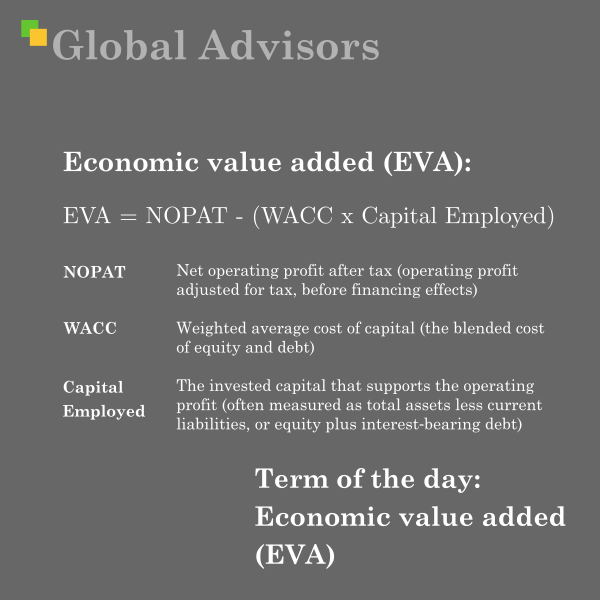

Term: Economic profit / Economic value added (EVA)Economic value added (EVA) is a measure of a company’s financial performance that captures the surplus generated over and above the required return on the capital invested in the business. It is an implementation of the residual income concept: the profit left after charging the business for the full economic cost of the capital employed.

Interpretation: A positive EVA indicates the business is generating returns in excess of its cost of capital and therefore creating shareholder value. A negative EVA indicates the opposite — the firm’s operations are not earning the return investors require. Why EVA matters for strategy and performance management

Key components and typical Stern Stewart adjustments

Simple numeric example

Practical strengths

Limitations and risks

When to use and implementation considerations

Relationship to other concepts

Relevant strategy theorist: G. Bennett Stewart IIIG. Bennett Stewart III (commonly cited as Bennett Stewart) is the central figure in the development and commercialisation of EVA. As co-founder of Stern Stewart & Co., he led the effort to translate residual-income theory into a practical, widely adoptable performance metric and management system that executives and boards could use to manage for shareholder value. Backstory and relationship to EVA

Biography (career highlights and contributions)

Context and critique in strategy literature

Concluding noteEVA is a powerful tool when used as part of a broader value-based management system: it converts the abstract idea of “creating shareholder value” into a measurable, actionable figure that ties operational results to the cost of capital. G. Bennett Stewart III’s contribution was to turn that concept into a widely adopted management practice by defining adjustments, demonstrating application across real companies, and promoting EVA as the backbone of incentive and capital-allocation systems. Use it with clear rules, transparent governance and complementary strategic metrics to avoid the common pitfalls.

Economic value added (EVA) is a measure of financial performance that captures the surplus generated above the required return on the capital invested in the business: the profit left after charging the business for the full economic cost of the capital employed.

|

| |

| |

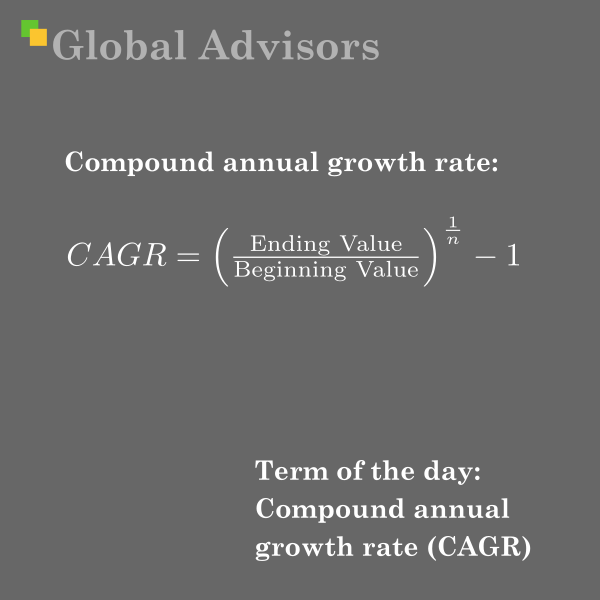

Term: Compound annual growth rate (CAGR)Compound annual growth rate (CAGR) represents the annualised rate at which an investment, business metric, or portfolio grows over a specified period, assuming that gains are reinvested each year and growth occurs at a steady, compounded pace. CAGR serves as a critical metric for both investors and business strategists due to its ability to smooth volatile performance into a single, comparable growth rate for analysis and forecasting. Definition and Calculation The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) equation is:

The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) represents the annualised rate at which an investment, business metric, or portfolio grows over a specified period, assuming that gains are reinvested each year and growth occurs at a steady, compounded pace. CAGR serves as a critical metric for both investors and business strategists due to its ability to smooth volatile performance into a single, comparable growth rate for analysis and forecasting.

where:

Applications and Significance

CAGR does not reflect actual annual returns; instead, it depicts a hypothetical steady rate, offering clarity when reviewing performance over inconsistent periods or for benchmarking against industry standards. It is widely used in strategy consulting, financial modelling, budgeting, and decision analysis. Leading Strategy Theorist: Alfred Rappaport Rappaport’s seminal book, Creating Shareholder Value, published in 1986 (and subsequently updated), positioned value creation as the primary objective of management, with CAGR-based metrics being critical to tracking value growth through discounted cash flow analysis. His work profoundly shaped the discipline of value-based management, which relies on compounding growth rates both in forecasting and in performance assessment. Throughout his career, Rappaport has acted as both an academic and adviser, influencing leading corporates and institutional investors by promoting disciplined investment criteria and strategic decision-making grounded in robust, compounding growth metrics like CAGR. His recognition of the importance of compound returns as opposed to simple arithmetic averages underpins the widespread adoption of CAGR in professional practice.

|

| |

| |

Quote: Benjamin Graham - The “father of value investing”“The worth of a business is measured not by what has been put into it, but by what can be taken out of it.” - Benjamin Graham - The “father of value investing”The quote, “The worth of a business is measured not by what has been put into it, but by what can be taken out of it,” is attributed to Benjamin Graham, a figure widely acknowledged as the “father of value investing”. This perspective reflects Graham’s lifelong focus on intrinsic value and his pivotal role in shaping modern investment philosophy. Context and Significance of the Quote This statement underscores Graham’s central insight: the value of a business does not rest in the sum of capital, effort, or resources invested, but in its potential to generate future cash flows and economic returns for shareholders. It rebuffs the superficial appeal to sunk costs or historical inputs and instead centres evaluation on what the business can practically yield for its owners—capturing a core tenet of value investing, where intrinsic value outweighs market sentiment or accounting measures. This approach has not only revolutionised equity analysis but has become the benchmark for rational, objective investment decision-making amidst market speculation and emotion. About Benjamin Graham Born in 1894 in London and emigrating to New York as a child, Benjamin Graham began his career in a tumultuous era for financial markets. Facing personal financial hardship after his father’s death, Graham still excelled academically and graduated from Columbia University in 1914, forgoing opportunities to teach in favour of a position on Wall Street. His career was marked by the establishment of the Graham–Newman Corporation in 1926, an investment partnership that thrived through the Great Depression—demonstrating the resilience of his theories in adverse conditions. Graham’s most influential works, Security Analysis (1934, with David Dodd) and The Intelligent Investor (1949), articulated the discipline of value investing and codified concepts such as “intrinsic value,” “margin of safety”, and the distinction between investment and speculation. Unusually, Graham placed great emphasis on independent thinking, emotional detachment, and systematic security analysis, encouraging investors to focus on underlying business fundamentals rather than market fluctuations. His professional legacy was cemented through his mentorship of legendary investors such as Warren Buffett, John Templeton, and Irving Kahn, and through the enduring influence of his teachings at Columbia Business School and elsewhere. Leading Theorists in Value Investing and Company Valuation Value investing as a discipline owes much to Graham but was refined and advanced by several influential theorists:

Other schools of thought in corporate valuation and investor returns—such as those developed by John Burr Williams and Aswath Damodaran—further developed discounted cash flow analysis and the quantitative assessment of future earnings power, building on the original insight that a business’s worth resides in its capacity to generate distributable cash over time. Enduring Relevance Graham’s philosophy remains at the core of every rigorous approach to corporate valuation. The quote is especially pertinent in contemporary valuation debates, where the temptation exists to focus on investment scale, novelty, or historical spend, rather than sustainable, extractable value. In every market era, Graham’s legacy is a call to refocus on long-term economic substance over short-term narratives—“not what has been put into it, but what can be taken out of it”.

|

| |

| |

Term: Return on Net Assets (RONA), also commonly referred to as Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)Return on Net Assets (RONA), also commonly referred to as Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), is a profitability ratio that measures how efficiently a company generates net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) from its invested capital. The typical formula is: RONA (or ROIC) = NOPAT ÷ Invested Capital This metric assesses the return a business earns on the capital allocated to its core operations, excluding the effect of financial leverage and non-operating items. NOPAT is used as it reflects the after-tax profits generated purely from operations, providing a cleaner view of value creation for all providers of capital. Invested capital focuses on assets directly tied to operational performance: fixed assets such as property, plant and equipment, and net working capital (current operating assets less current operating liabilities). This construction ensures the measure remains aligned with how capital is deployed within the firm. RONA/ROIC enables investors, managers, and analysts to judge whether a company is generating returns above its cost of capital—a key determinant of value creation and strategic advantage. The ratio also acts as a benchmark for performance improvement and capital allocation decisions. Arguments for Using RONA/ROIC

Criticisms and Limitations

Leading Theorists and Strategic FoundationsAswath Damodaran and the authors of Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies—Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart, and David Wessels—are directly associated with the development, articulation, and scholarly propagation of concepts like RONA and ROIC. Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart, and David WesselsAs co-authors of the definitive text Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (first published in 1990, now in its 7th edition), Koller, Goedhart, and Wessels have provided the most detailed and widely adopted frameworks for calculating, interpreting, and applying ROIC in both academic and practitioner circles. Their work systematised the relationship between ROIC, cost of capital, and value creation, embedding this metric at the heart of modern strategic finance and value-based management. They emphasise that only companies able to sustain ROIC above their cost of capital create lasting economic value, and their approach is rigorous in ensuring clarity of calculation (advocating NOPAT and properly defined invested capital for consistency and comparability). Their text is canonical in both MBA programmes and leading advisory practices, widely referenced in strategic due diligence, private equity, and long-term corporate planning. Aswath DamodaranAswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at the NYU Stern School of Business, is another seminal figure. His textbooks, including Investment Valuation and Damodaran on Valuation, champion the use of ROIC as a core measure of company performance. Damodaran’s extensive public lectures, datasets, and analytical frameworks stress the importance of analysing returns on invested capital and understanding how this interacts with growth and risk in both investment analysis and strategic decision-making. Damodaran’s work is highly practical, meticulously clarifying issues in the calculation and interpretation of ROIC, especially around treatment of operating leases, goodwill, and intangibles, and highlighting the complexities that confront both value investors and boards. His influence is broad, with his online resources and publications serving as go-to technical references for professionals and academics alike. Both Damodaran and the Valuation authors are credited with shaping the field’s understanding of RONA/ROIC’s strategic implications and embedding this measure at the core of value-driven management and investment strategy.

|

| |

| |

Quote: Aswath Damodaran - Professor, Valuation authority“There is a role for valuation at every stage of a firm’s life cycle.” - Aswath Damodaran - Professor, Valuation authorityThe firm life cycle—from inception and private ownership, through growth, maturity, and ultimately potential decline or renewal—demands distinct approaches to appraising value. Damodaran’s teaching and extensive writings consistently stress that whether a company is a start-up seeking venture funding, a mature enterprise evaluating capital allocation, or a business facing restructuring, rigorous valuation remains central to informed strategic choices. His observation is rooted in decades of scholarly analysis and practical engagement with valuation in corporate finance—arguing that effective valuation is not limited to transactional moments (such as M&A or IPOs), but underpins everything from resource allocation and performance assessment to risk management and governance. By embedding valuation across the firm life cycle, leaders can navigate uncertainty, optimise capital deployment, and align stakeholder interests, regardless of market conditions or organisational maturity. About Aswath Damodaran Aswath Damodaran is universally acknowledged as one of the world’s pre-eminent authorities on valuation. Professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business since 1986, Damodaran holds the Kerschner Family Chair in Finance Education. His academic lineage includes a PhD in Finance and an MBA from the University of California, Los Angeles, as well as an early degree from the Indian Institute of Management. Damodaran’s reputation extends far beyond academia. He is widely known as “the dean of valuation”, not only for his influential research and widely-adopted textbooks but also for his dedication to education accessibility—he makes his complete MBA courses and learning materials freely available online, thereby fostering global understanding of corporate finance and valuation concepts. His published work spans peer-reviewed articles in leading academic journals, practical texts on valuation and corporate finance, and detailed explorations of topics such as risk premiums, capital structure, and market liquidity. Damodaran’s approach combines rigorous theoretical frameworks with empirical clarity and real-world application, making him a key reference for practitioners, students, and policy-makers. Prominent media regularly seek his views on valuation, capital markets, and broader themes in finance. Leading Valuation Theorists – Backstory and Impact While Damodaran has shaped the modern field, the subject of valuation draws on the work of multiple generations of thought leaders.

Damodaran’s Place in the Lineage Damodaran’s distinctive contribution is the synthesis of classical theory with contemporary market realities. His focus on making valuation relevant “at every stage of a firm’s life cycle” bridges the depth of theoretical models with the dynamic complexity of today’s global markets. Through his teaching, prolific writing, and commitment to open-access learning, he has shaped not only valuation scholarship but also the way investors, executives, and advisors worldwide think about value creation and measurement.

|

| |

| |

Term: EBITDA multipleThe EBITDA multiple, also known as the enterprise multiple, is a widely used financial metric for valuing businesses, particularly in mergers and acquisitions and investment analysis. It is calculated by dividing a company’s Enterprise Value (EV) by its Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortisation (EBITDA). The formula can be expressed as: EBITDA Multiple = Enterprise Value (EV) ÷ EBITDA. Enterprise Value (EV) represents the theoretical takeover value of a business and is commonly computed as the market capitalisation plus total debt, minus cash and cash equivalents. By using EV (which is capital structure-neutral), the EBITDA multiple enables comparison across companies with differing debt and equity mixes, making it particularly valuable for benchmarking and deal-making in private equity, strategic acquisitions, and capital markets. Arguments for Using the EBITDA Multiple

Criticisms of the EBITDA Multiple

Related Strategy Theorist: Michael C. JensenThe evolution and widespread adoption of EBITDA multiples in valuation is closely linked to the rise of leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and private equity in the 1980s—a movement shaped and analysed by Michael C. Jensen, a foundational figure in corporate finance and strategic management. Michael C. Jensen (born 1939): During the 1980s, Jensen extensively researched the dynamics of leveraged buyouts and the use of debt in corporate restructuring, documenting how private equity sponsors used enterprise value and metrics like EBITDA multiples to value acquisition targets. He advocated for the use of cash flow–oriented metrics (such as EBITDA and free cash flow) as better indicators of firm value than traditional accounting profit measures, particularly in contexts where operating assets and financial structure could be separated. His scholarship not only legitimised and popularised such metrics among practitioners but also critically explored their limitations—addressing issues around agency costs, capital allocation, and the importance of considering cash flows over accounting earnings. In summary, the EBITDA multiple is a powerful and popular tool for business valuation—valued for its simplicity and broad applicability, but its limitations require careful interpretation and complementary analysis. Michael C. Jensen’s scholarship frames both the advantages and necessary caution in relying on single-value multiples in strategy and valuation.

|

| |

| |

Quote: Bill Miller - Investor, fund manager“One of the most powerful sources of mispricing is the tendency to over-weight or over-emphasize current conditions.” - Bill Miller - Investor, fund managerBill Miller is a renowned American investor and fund manager, most prominent for his extraordinary tenure at Legg Mason Capital Management where he managed the Value Trust mutual fund. Born in 1950 in North Carolina, Miller graduated with honours in economics from Washington and Lee University in 1972 and went on to serve as a military intelligence officer. He later pursued graduate studies in philosophy at Johns Hopkins University before advancing into finance, embarking on a career that would reshape perceptions of value investing. Miller joined Legg Mason in 1981 as a security analyst, eventually becoming chairman and chief investment officer for the firm and its flagship fund. Between 1991 and 2005, the Legg Mason Value Trust—under Miller’s stewardship—outperformed the S&P 500 for a then-unprecedented 15 consecutive years. This performance earned Miller near-mythical status within investment circles. However, the 2008 financial crisis, where he was heavily exposed to collapsing financial stocks, led to significant losses and a period of high-profile criticism. Yet Miller’s intellectual rigour and willingness to adapt led him to recover, founding Miller Value Partners and continuing to contribute important insights to the field. The context of Miller’s quote lies in his continued attention to investor psychology and behavioural finance. His experience—through market booms, crises, and recoveries—led him to question conventional wisdom around value investing and to recognise how often investors, swayed by the immediacy of current economic and market conditions, inaccurately price assets by projecting the present into the future. This insight is rooted both in academic research and in practical experience during periods such as the technology bubble, where the market mispriced risk and opportunity by over-emphasising prevailing narratives. Miller’s work and this quote sit within the broader tradition of theorists who have examined mispricing, market psychology, and the fallibility of investor judgement:

Bill Miller’s career is both a case study and a cautionary tale of these lessons in action. His perspective emphasises that value emerges over time, and only those who look beyond the prevailing winds of sentiment are positioned to capitalise on genuine mispricing. The tendency to overvalue present conditions is perennial, but so too are the opportunities for those who resist it.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |