| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Our selection of the top business news sources on the web. |

| |

| |

| |

Quote: William F. Sharpe - Nobel Laureate in Economics“Question not only everybody else’s work, but question your own work as you do it, let alone after it’s done.” - William F. Sharpe - Nobel Laureate in EconomicsWilliam F. Sharpe’s advice—to “question not only everybody else’s work, but question your own work as you do it, let alone after it’s done”—reflects the relentless intellectual self-scrutiny that has defined his career and shaped the field of financial economics. Sharpe delivered this insight in a 2004 Nobel Prize interview, recalling how the discipline of constant self-questioning was instilled in him by his mentor Armen Alchian at UCLA. The ethic to act as one’s own toughest reviewer permeated Sharpe’s approach to research and innovation, driving his work to the highest standards of analytical rigour throughout a career that upended how global markets understand risk and return. Sharpe’s journey began in Boston in 1934 and traversed the turbulence of war-era America, eventually landing him at UCLA, where changing his studies from medicine to economics would alter the trajectory of his life. Inspired by Alchian’s rigour and by J. Fred Weston’s introduction to the still-nascent field of portfolio theory, Sharpe was quickly drawn to the beauty of mathematical logic applied to real-world economic problems. He honed his analytical skill during years of study and early research at RAND Corporation, where he encountered Harry Markowitz, whose pioneering work on portfolio selection laid the groundwork for Sharpe’s own breakthroughs. It was Sharpe's drive to question assumptions and his openness to self-critique that enabled him to distil Markowitz’s complex mean-variance model into the elegant Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). This model became the backbone of modern finance, fundamentally altering how the risk and return of risky assets are priced and giving birth to the now ubiquitous concept of “beta.” Published in 1964 after initial scepticism from academic gatekeepers, Sharpe’s work, completed in parallel with Jack Treynor, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin, revolutionised both theory and practice. The CAPM forms the intellectual infrastructure for everything from index fund investing to performance benchmarking, nurturing a global culture in which prudent risk-taking is measurable, comparable, and improvable. Sharpe’s subsequent innovations, including the Sharpe Ratio, reinforced his belief that rigorous, repeatable self-examination is essential for practical financial decision-making as well as academic advancement. Sharpe’s career is remarkable not just for his theoretical contributions, but for his insistence on connecting model with reality. He split his time between academia (with appointments at the University of Washington, Stanford, and elsewhere) and hands-on consulting, founding Sharpe-Russell Research to advise some of the world’s largest investors and co-founding Financial Engines, an early pioneer in digital investment advice. Throughout, he has focused on making abstract models relevant for individual and institutional investors, and on adapting theory to the rapidly evolving realities of global capital markets. His Nobel Prize in 1990, shared with Markowitz and Merton Miller, formalised his status as a founder of modern financial economics. The backstory of Sharpe’s impact is inseparable from the broader evolution of risk and investment theory in the twentieth century. Harry Markowitz, often considered the father of modern portfolio theory, provided the first quantitative framework for balancing risk and return through diversification. Markowitz’s work enabled rigorous measurement of portfolio variance and set the stage for Sharpe’s insight that only systematic, market-related risk is priced in rational markets. Merton Miller, the other co-recipient of the 1990 Nobel, contributed critical insights into corporate finance, market efficiency, and capital structure, further solidifying the empirical and analytical basis for much of today’s investment practice. Sharpe’s quote, therefore, encapsulates the ethos of the scientific method as it applies to finance: progress is made not through mere acceptance or simple iteration, but through persistent, honest, and sometimes uncomfortable dialogue with one’s own assumptions and results. This disposition has not only underpinned Sharpe’s seminal achievements—transforming how markets price risk, fostering the index fund revolution, and shaping the metrics by which investment success is measured—but also compelled subsequent generations of theorists and practitioners to perpetually test, critique, and refine the frameworks upon which the security of trillions of dollars depends.

|

| |

| |

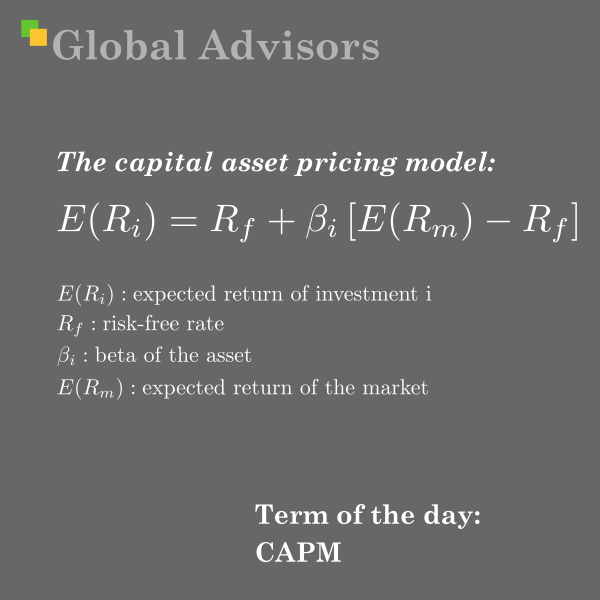

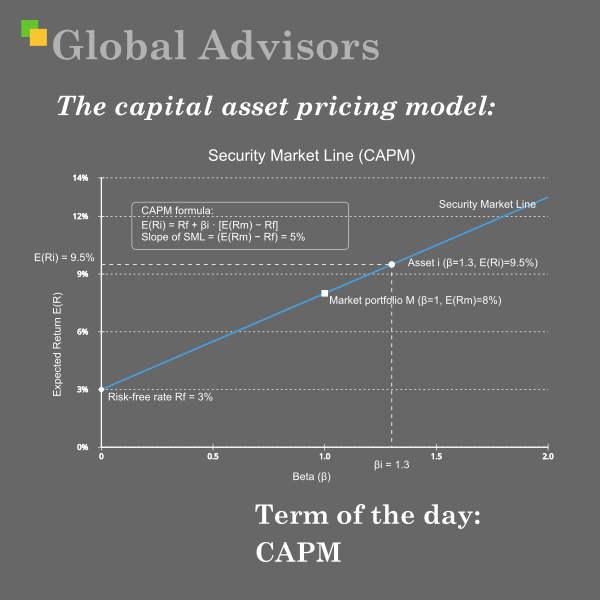

Term: The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)A Comprehensive Analysis of Risk, Return and Modern Portfolio TheoryThe Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) stands as one of the most influential theoretical frameworks in modern finance, fundamentally transforming how investors, analysts, and financial theorists understand the relationship between risk and expected returns. Developed simultaneously by four brilliant economists in the early 1960s—William Sharpe, Jack Treynor, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin—CAPM emerged from Harry Markowitz's ground-breaking work on Modern Portfolio Theory to provide a mathematically elegant solution to the age-old investment question: what return should investors expect for bearing a particular level of risk? This revolutionary model established that only systematic, non-diversifiable risk should command a risk premium in efficient markets, suggesting that investors can achieve optimal portfolio performance through broad diversification whilst earning returns commensurate with their risk tolerance. The model's profound impact on financial practice cannot be overstated, as it provided the theoretical foundation for index fund investing, influenced regulatory frameworks such as the Prudent Investor Rule, and continues to guide trillions of dollars in institutional investment decisions worldwide, despite ongoing academic debates about its empirical validity and restrictive assumptions. Definition and Core Conceptual FrameworkThe Capital Asset Pricing Model represents a mathematical framework that describes the linear relationship between systematic risk and expected return for individual securities and portfolios in financial markets. At its essence, CAPM posits that the expected return of any risky asset can be calculated by adding a risk premium to the risk-free rate, where the risk premium is determined by the asset's sensitivity to market movements multiplied by the market risk premium. This elegantly simple insight revolutionised investment theory by providing a quantitative method for determining whether securities are fairly priced relative to their risk characteristics. The model's foundational principle rests on the distinction between systematic risk, which affects the entire market and cannot be eliminated through diversification, and idiosyncratic risk, which is specific to individual securities and can be diversified away. CAPM argues that rational investors should only be compensated for bearing systematic risk, as idiosyncratic risks can be eliminated through proper portfolio construction. This insight led to the profound realisation that holding a diversified portfolio aligned with market weightings represents the optimal investment strategy for most investors, as it maximises expected returns for a given level of systematic risk exposure. The mathematical expression of CAPM takes the form of a linear equation where the expected return of asset i equals the risk-free rate plus beta multiplied by the market risk premium. Beta, the model's central risk measure, quantifies how much an asset's returns tend to move in relation to overall market movements, with a beta of 1.0 indicating returns that move in perfect synchronisation with the market, values above 1.0 suggesting amplified market sensitivity, and values below 1.0 indicating more stable, less volatile performance characteristics. The theoretical elegance of CAPM lies in its ability to reduce the complex portfolio selection problem identified by Markowitz into a simple, two-fund theorem. According to this principle, all rational investors should hold portfolios consisting of only two components: the risk-free asset and the market portfolio of risky assets, with individual risk preferences determining the specific allocation between these two elements. This insight dramatically simplified investment decision-making whilst providing a coherent framework for understanding how asset prices should be determined in efficient markets. Historical Development and EvolutionThe development of the Capital Asset Pricing Model represents one of the most remarkable examples of simultaneous scientific discovery in the history of economic thought, with four economists independently arriving at essentially identical conclusions during the early 1960s. This extraordinary convergence of intellectual effort emerged from the fertile ground prepared by Harry Markowitz's pioneering 1952 paper on portfolio selection, which had established the mathematical foundation for modern portfolio theory but left unresolved the practical challenge of determining appropriate expected returns for individual securities. Harry Markowitz had fundamentally transformed investment analysis by introducing rigorous mathematical methods to portfolio construction, demonstrating that investors could reduce portfolio risk through diversification without necessarily sacrificing expected returns. His work established the efficient frontier concept, showing that optimal portfolios could be constructed to maximise expected return for any given level of risk. However, Markowitz's original formulation required investors to estimate expected returns, variances, and covariances for all securities under consideration—a computationally intensive process that seemed impractical for real-world application with large numbers of securities. The stage was set for further innovation when Markowitz began collaborating with his graduate student William Sharpe at UCLA in the late 1950s. Sharpe, who had initially been disappointed to discover that financial practice relied on "rule of thumb" rather than rigorous theory, became determined to apply newly developed computer programs and mathematical models to quantify market processes. Working under Markowitz's informal guidance, Sharpe developed what would become his doctoral dissertation, exploring ways to simplify the portfolio selection problem through the introduction of a single-factor model that related individual security returns to a common market factor. Simultaneously, Jack Treynor was grappling with similar questions from a practitioner's perspective at Arthur D. Little consulting firm. Having studied mathematics at Haverford College before earning an MBA from Harvard Business School, Treynor had become frustrated with the arbitrary nature of discount rate selection in corporate finance decisions. During a three-week summer vacation in 1958, working in a cottage in Evergreen, Colorado, Treynor produced 44 pages of mathematical notes addressing the relationship between risk and appropriate discount rates—work that would form the kernel of what became known as CAPM. John Lintner at Harvard Business School approached the capital asset valuation problem from yet another angle, focusing on the corporate perspective of firms issuing securities rather than the individual investor's portfolio selection challenge. His work complemented the insights being developed by Sharpe and Treynor, though the various researchers remained largely unaware of each other's parallel efforts for several years. Jan Mossin, working independently in Norway, completed this quartet of simultaneous discoverers, contributing his own mathematical formulation of the asset pricing relationship. The publication history of these seminal contributions reveals the initial scepticism that greeted this revolutionary theory. Sharpe's paper, submitted to the Journal of Finance in 1962, was initially rejected by referees who deemed its assumptions too restrictive and its results "uninteresting". Only after the journal changed editors was the paper finally published in 1964, ultimately becoming one of the most cited works in financial economics. Treynor's contribution faced an even more challenging publication path—his early draft circulated among the financial cognoscenti for decades before formal publication, earning him recognition as a foundational contributor despite the delayed formal acknowledgment. Mathematical Foundation and Analytical FrameworkThe mathematical elegance of the Capital Asset Pricing Model lies in its ability to distil the complex relationship between risk and return into a single linear equation that captures the essential trade-offs facing investors in capital markets. The CAPM formula represents far more than a simple computational tool—it embodies a comprehensive theory of how rational investors should price risky assets in equilibrium:

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) quantifies the link between an asset’s systematic risk and its expected return, proposing that investors require higher returns for taking on increased market risk.

Each component of the CAPM equation carries profound theoretical significance that extends well beyond its mathematical representation. The risk-free rate Ri serves as the foundational baseline return that investors can earn without bearing any uncertainty, typically proxied by government treasury securities due to their minimal default risk. This component acknowledges the time value of money principle, ensuring that all investment returns are evaluated relative to what could be earned from completely safe alternatives. The choice of appropriate risk-free rate proxy has evolved over time, with ten-year treasury yields becoming the standard benchmark for long-term investment analysis, though shorter-term rates may be more appropriate for specific applications. Betai represents the model's central innovation, providing a standardised measure of systematic risk that captures how individual securities or portfolios respond to market-wide movements. Unlike traditional risk measures that focused on total volatility, beta isolates only that portion of risk that cannot be eliminated through diversification—the systematic risk that affects the entire market. Securities with betas greater than 1.0 exhibit amplified responses to market movements, experiencing larger gains during market upswings and steeper losses during downturns. Conversely, securities with betas below 1.0 demonstrate more stable performance characteristics, providing some insulation from market volatility whilst generally participating in market trends to a lesser degree. The market risk premium (E(Rm) - Rf) represents the additional return that investors demand for bearing the uncertainty inherent in holding the overall market portfolio rather than risk-free securities. This component reflects the collective risk aversion of market participants and tends to fluctuate over time based on economic conditions, investor sentiment, and broader market dynamics. Historical estimates of the equity risk premium have varied considerably, with long-term averages typically ranging between 5-8% annually, though shorter-term variations can be substantially larger. The linearity of the CAPM relationship embodies several profound theoretical implications that distinguish it from alternative asset pricing models. The linear form suggests that risk premiums increase proportionally with beta, meaning that an asset with twice the systematic risk should command twice the risk premium. This proportionality assumption has been subject to extensive empirical testing, with mixed results that have spawned numerous alternative models attempting to capture non-linear risk-return relationships. Beta estimation itself represents a sophisticated econometric challenge that requires careful consideration of multiple factors including the choice of market proxy, measurement period, return frequency, and statistical methodology. Most practical applications calculate beta using ordinary least squares regression analysis, regressing individual asset returns against market returns over historical periods ranging from one to five years. However, the backward-looking nature of historical beta estimation raises important questions about its predictive validity, leading some practitioners to employ more sophisticated techniques such as adjusted beta calculations that account for the tendency of individual security betas to converge toward 1.0 over time.

The graphic illustrates the Security Market Line (CAPM), plotting expected return against beta. The line intercepts the y-axis at the risk?free rate (3%), rises with a slope equal to the market risk premium (5%), and passes through the market portfolio at ? = 1 (8%). A sample asset at ? = 1.3 sits on the line at 9.5%, showing how CAPM links required return to systematic risk.

William Sharpe: The Primary Architect and Nobel LaureateWilliam Forsyth Sharpe emerges as the most prominent figure associated with the Capital Asset Pricing Model, not merely due to his Nobel Prize recognition in 1990, but because of his sustained contributions to financial theory and his role in bridging academic research with practical investment applications. Born on 16 June 1934 in Boston, Massachusetts, Sharpe's intellectual journey towards developing CAPM began during a peripatetic childhood shaped by his father's service in the National Guard during World War II. The family's eventual settlement in Riverside, California, provided the stable environment where young Sharpe's analytical talents could flourish, leading to his graduation from Riverside Polytechnic High School in 1951. Sharpe's initial academic trajectory reflected the uncertainty typical of bright young students exploring their intellectual interests. Beginning his university education at UC Berkeley with intentions of pursuing medicine, he quickly discovered that his true passions lay elsewhere and transferred to UCLA to study business administration. However, even this focus proved insufficiently engaging, as Sharpe found accounting uninspiring and gravitated instead toward economics, where he encountered two professors who would profoundly influence his intellectual development: Armen Alchian, who became his mentor, and J. Fred Weston, who first introduced him to Harry Markowitz's revolutionary papers on portfolio theory. The pivotal moment in Sharpe's career came through his association with the RAND Corporation, which he joined in 1956 immediately after graduation whilst simultaneously beginning doctoral studies at UCLA. This unique position at the intersection of academic research and practical problem-solving provided the ideal environment for developing the theoretical insights that would culminate in CAPM. At RAND, Sharpe encountered Harry Markowitz directly, leading to an informal but highly productive advisor-advisee relationship that would shape the trajectory of modern financial theory. The intellectual genesis of CAPM can be traced to Sharpe's doctoral dissertation work in the early 1960s, where he grappled with the practical limitations of Markowitz's mean-variance optimisation framework. Whilst Markowitz had demonstrated the mathematical principles underlying efficient portfolio construction, the computational requirements of his approach seemed prohibitive for real-world application with large numbers of securities. Sharpe's breakthrough insight involved simplifying this complex optimisation problem through the introduction of a single-factor model that related individual security returns to a broad market index. Sharpe's 1961 dissertation included an early version of what would become the security market line, demonstrating the linear relationship between expected return and systematic risk that forms the heart of CAPM. However, the path from academic insight to published theory proved challenging, as the financial economics establishment initially struggled to appreciate the revolutionary implications of this work. When Sharpe submitted his refined CAPM paper to the Journal of Finance in 1962, referees rejected it as uninteresting and overly restrictive in its assumptions. Only after the journal's editorial staff changed was the paper finally published in 1964, launching what would become one of the most influential theories in modern finance. Following the publication of his seminal CAPM paper, Sharpe's career trajectory reflected his commitment to both theoretical development and practical application of financial insights. His move to the University of Washington in 1961 provided the academic platform for refining and extending his theoretical work, whilst his subsequent positions at UC Irvine and Stanford University established him as one of the leading figures in the emerging field of financial economics. Throughout this period, Sharpe continued to innovate, developing the Sharpe ratio for risk-adjusted performance analysis, contributing to options valuation methodology, and pioneering returns-based style analysis for investment fund evaluation. Perhaps most significantly for the practical application of financial theory, Sharpe's work provided the intellectual foundation for the index fund revolution that transformed investment management. His demonstration that broad market diversification represented the optimal strategy for most investors directly supported the development of low-cost, passively managed investment vehicles that now manage trillions of dollars worldwide. This practical impact extended beyond portfolio management to influence regulatory frameworks, with Sharpe's insights contributing to the evolution of fiduciary standards and prudent investor guidelines. The recognition of Sharpe's contributions culminated in his receipt of the 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, shared with Harry Markowitz and Merton Miller, "for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics". The Nobel Committee specifically recognised Sharpe's development of CAPM as providing the first coherent framework for understanding how risk should affect expected returns in capital markets. This recognition acknowledged not only the theoretical elegance of CAPM but also its profound practical implications for investment management, corporate finance, and financial regulation. Sharpe's post-Nobel career demonstrated his continued commitment to bridging academic theory and practical application. His founding of Sharpe-Russell Research in 1986, in collaboration with the Frank Russell Company, focused on providing asset allocation research and consulting services to pension funds and foundations. This venture allowed Sharpe to implement the theoretical insights of CAPM and related models in real-world institutional investment contexts, demonstrating the practical value of rigorous financial theory whilst identifying areas where theoretical models required refinement or extension. The intellectual legacy of William Sharpe extends far beyond the specific mathematical formulation of CAPM to encompass a broader vision of how financial markets should function and how investors should approach portfolio construction. His work established the theoretical foundation for understanding that diversification represents the only "free lunch" available to investors, whilst simultaneously demonstrating that attempts to outperform market benchmarks through security selection or market timing face significant theoretical and practical obstacles. These insights continue to influence investment philosophy and practice decades after their initial formulation, testament to the enduring value of Sharpe's contributions to financial understanding. Applications and Practical ImplementationThe practical applications of the Capital Asset Pricing Model extend far beyond academic theorising, fundamentally transforming how financial professionals approach investment valuation, portfolio construction, and risk management across diverse market contexts. The model's primary application lies in determining appropriate required rates of return for individual securities and portfolios, providing a systematic framework for evaluating whether investments are fairly priced relative to their risk characteristics. This capability has proven invaluable for investment analysts, corporate finance professionals, and institutional portfolio managers seeking objective methods for comparing investment opportunities. In corporate finance applications, CAPM serves as the foundation for cost of equity calculations that drive fundamental valuation decisions including capital budgeting, merger and acquisition analysis, and strategic planning initiatives. Companies routinely employ CAPM-derived discount rates to evaluate potential investment projects, ensuring that capital allocation decisions reflect appropriate risk adjustments. The model's ability to provide standardised risk measures enables companies to compare projects across different business units and geographic regions, facilitating more informed strategic decision-making processes. The implementation of CAPM in institutional investment management has perhaps generated the most significant practical impact, providing the theoretical justification for passive index investing strategies that now dominate large portions of global capital markets. Sharpe's insight that the market portfolio represents the optimal risky asset holding for most investors directly supported the development of broad-based index funds that seek to replicate market returns whilst minimising costs and tracking errors. This application has proven particularly influential in pension fund management, where fiduciary responsibilities require systematic approaches to risk management and return optimisation. Portfolio managers utilise CAPM principles to construct efficient portfolios that balance risk and return considerations according to client preferences and constraints. The model's two-fund theorem suggests that optimal portfolio construction involves determining the appropriate allocation between risk-free assets and a diversified market portfolio, with individual risk tolerance determining the specific split. This framework has simplified portfolio management whilst providing a coherent theoretical foundation for explaining investment strategies to clients and regulatory authorities. The practical implementation of CAPM requires careful attention to several technical considerations that can significantly impact its effectiveness. Beta estimation presents particular challenges, as historical relationships may not accurately predict future risk characteristics, especially during periods of structural market change or economic transition. Many practitioners employ adjusted beta calculations that incorporate regression toward the mean tendencies, whilst others utilise fundamental beta estimation techniques based on company-specific operational and financial characteristics. Risk-free rate selection represents another critical implementation consideration, as the choice of benchmark can materially affect required return calculations. Most applications utilise government treasury securities as risk-free proxies, with the specific maturity selected to match the investment horizon under consideration. However, during periods of financial stress or when analysing international investments, the assumption of truly risk-free government securities may require careful reassessment. Market portfolio proxy selection similarly affects practical CAPM implementation, as the theoretical market portfolio of all risky assets cannot be directly observed or replicated. Most applications employ broad equity indices such as the S&P 500 as market proxies, though this approach potentially introduces biases when analysing non-equity investments or international securities. Some practitioners employ more comprehensive market proxies that include bonds, real estate, and international assets, though data availability and computational complexity often limit such approaches. The emergence of factor-based investing strategies represents a significant evolution in CAPM application, acknowledging that additional systematic risk factors beyond market beta may explain security returns. The Fama-French three-factor model and its subsequent extensions incorporate size, value, momentum, and quality factors alongside traditional market risk measures, providing more nuanced approaches to risk-adjusted return analysis. These enhanced models maintain the theoretical framework established by CAPM whilst addressing some of its empirical limitations in explaining cross-sectional return variations. Regulatory applications of CAPM have proven particularly influential in establishing standards for prudent investment management and fiduciary responsibility. The Prudent Investor Rule, which governs investment decision-making for trust and pension fund management, draws heavily on modern portfolio theory principles established by Markowitz and extended through CAPM. These regulatory frameworks recognise that diversification and systematic risk management, rather than individual security selection, should form the foundation of responsible institutional investment management. Limitations and Theoretical CriticismsDespite its theoretical elegance and widespread practical adoption, the Capital Asset Pricing Model faces substantial criticisms that have sparked decades of academic debate and led to the development of numerous alternative asset pricing models. These limitations stem from both the restrictive assumptions underlying CAPM's theoretical construction and empirical evidence suggesting that the model's predictions do not consistently match observed market behaviour across different time periods and market conditions. The most fundamental criticism of CAPM concerns its reliance on highly restrictive assumptions that appear inconsistent with real-world market behaviour. The model assumes that all investors are rational, risk-averse utility maximisers who possess identical information sets and time horizons—assumptions that behavioural finance research has repeatedly challenged. Real investors demonstrate systematic biases, varying degrees of sophistication, and heterogeneous preferences that can lead to market inefficiencies and pricing anomalies that CAPM cannot explain. Market efficiency assumptions embedded within CAPM represent another significant limitation, as the model requires that securities markets be perfectly competitive with instantaneous price adjustments to reflect all available information. Empirical evidence suggests that markets exhibit various forms of inefficiency, including momentum effects, mean reversion patterns, and predictable seasonal variations that contradict the efficient market hypothesis underlying CAPM. These inefficiencies create opportunities for active investment strategies that CAPM theory suggests should not exist in equilibrium. The assumption of constant investment opportunities over time represents a particularly problematic limitation, as CAPM treats risk-free rates, market risk premiums, and beta coefficients as static parameters when they clearly fluctuate substantially over time. The risk-free rate varies continuously with monetary policy decisions and economic conditions, whilst equity risk premiums demonstrate significant cyclical and secular variations that can materially impact expected return calculations. Similarly, individual security and portfolio betas exhibit instability over time, raising questions about the predictive validity of historical beta estimates. Empirical testing of CAPM has revealed numerous anomalies that challenge the model's explanatory power and practical validity. The size effect, first documented by researchers including Fama and French, demonstrates that small-capitalisation stocks tend to earn higher risk-adjusted returns than CAPM predicts, suggesting that market capitalisation represents an additional systematic risk factor not captured by beta alone. Similarly, the value effect shows that stocks with low price-to-book ratios tend to outperform growth stocks after adjusting for beta risk, indicating that valuation characteristics contain systematic risk information beyond that captured by market sensitivity. The low-beta anomaly represents perhaps the most direct challenge to CAPM's central prediction, as empirical evidence suggests that low-beta stocks tend to earn higher risk-adjusted returns than high-beta stocks, contradicting the model's fundamental assertion that expected returns should increase linearly with systematic risk. This finding has persisted across different time periods and market conditions, suggesting a fundamental flaw in CAPM's risk-return relationship rather than temporary market inefficiency. Beta estimation challenges represent significant practical limitations that affect CAPM's implementation effectiveness. Historical beta calculations depend critically on the choice of measurement period, return frequency, and market proxy, with different specifications potentially yielding substantially different beta estimates for the same security. The assumption that historical relationships will persist into the future may be particularly problematic for companies experiencing structural changes, industry disruptions, or significant operational modifications that alter their fundamental risk characteristics. The single-factor structure of CAPM represents a theoretical limitation that numerous researchers have attempted to address through multi-factor model development. The Arbitrage Pricing Theory, developed by Stephen Ross, provides a more flexible framework that can accommodate multiple systematic risk factors whilst maintaining theoretical consistency. Similarly, the Fama-French factor models and their extensions incorporate additional systematic risk factors including size, value, momentum, and profitability that appear to explain cross-sectional return variations more effectively than beta alone. Transaction costs and market frictions, explicitly assumed away by CAPM, represent significant practical limitations that affect real-world investment implementation. The model's assumption of unlimited borrowing and lending at the risk-free rate clearly does not hold in practice, as investors face borrowing constraints and credit risk considerations that affect their actual investment opportunities. Similarly, transaction costs, tax considerations, and liquidity constraints can materially affect portfolio construction decisions in ways that CAPM does not address. International applications of CAPM face additional limitations related to currency risk, market segmentation, and varying regulatory environments that complicate the model's implementation across borders. The International Capital Asset Pricing Model attempts to address some of these concerns by incorporating exchange rate risk as an additional systematic factor, though practical implementation remains challenging due to the complexity of international risk relationships. Modern Relevance and Theoretical ExtensionsThe enduring influence of the Capital Asset Pricing Model in contemporary finance extends far beyond its original formulation, serving as the foundational framework from which numerous sophisticated asset pricing models have evolved to address the complexities of modern global financial markets. Whilst academic research has identified significant limitations in CAPM's empirical performance, the model's theoretical insights continue to guide investment practice, regulatory policy, and financial education worldwide, demonstrating the remarkable resilience of its core conceptual contributions. Modern portfolio management increasingly employs factor-based investing strategies that build upon CAPM's systematic risk framework whilst incorporating additional risk dimensions identified through empirical research. The Fama-French three-factor model represents the most widely adopted extension, adding size and value factors to the original market factor to better explain cross-sectional return variations. This model's success in capturing return patterns that CAPM alone cannot explain has led to its widespread adoption in academic research and practical investment applications, particularly in portfolio performance evaluation and risk-adjusted return analysis. The evolution toward multi-factor models has accelerated with the development of increasingly sophisticated quantitative investment strategies that seek to harvest systematic risk premiums across multiple dimensions. Modern factor investing encompasses momentum, quality, low-volatility, and profitability factors alongside the traditional size and value characteristics, creating a rich taxonomy of systematic risk sources that extends CAPM's single-factor structure. These developments represent evolutionary refinements rather than revolutionary departures from CAPM's core insights about systematic risk and diversification benefits. Smart beta and strategic beta investment strategies exemplify how CAPM's theoretical framework continues to influence modern portfolio construction methodology. These approaches maintain CAPM's emphasis on systematic risk management whilst employing alternative weighting schemes designed to capture specific risk premiums or reduce particular risk exposures. The theoretical foundation provided by CAPM enables practitioners to understand these strategies as variations on the fundamental theme of balancing systematic risk exposure with expected return generation. Risk management applications of CAPM have evolved considerably to address the model's limitations whilst preserving its analytical convenience and theoretical coherence. Modern risk management systems often employ CAPM-derived beta estimates as starting points for more sophisticated risk models that incorporate regime shifts, time-varying parameters, and non-linear risk relationships. These enhanced approaches acknowledge CAPM's limitations whilst leveraging its systematic risk framework to provide practical risk measurement and management tools. The influence of CAPM on regulatory frameworks and professional standards remains profound, with modern investment regulations continuing to reflect the model's emphasis on diversification and systematic risk management. The Prudent Investor Rule and similar fiduciary standards worldwide incorporate CAPM-inspired concepts about the primacy of asset allocation decisions and the importance of systematic risk management over security selection. These regulatory applications demonstrate how CAPM's theoretical insights have become embedded in the institutional framework governing professional investment management. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing represents a contemporary application area where CAPM's framework provides valuable analytical structure despite requiring significant conceptual extensions. ESG risk factors can be understood as additional systematic risk dimensions that may command risk premiums in the same manner as traditional financial risk factors. This perspective enables the integration of sustainability considerations into traditional risk-return frameworks whilst maintaining analytical coherence and comparability with conventional investment approaches. The emergence of alternative risk premiums in hedge fund and institutional investing strategies reflects CAPM's continuing influence on how investment professionals conceptualise systematic risk and return relationships. Strategies focused on harvesting volatility risk premiums, credit risk premiums, and term structure risk premiums all build upon CAPM's fundamental insight that systematic risk exposure should be rewarded with commensurate expected returns. These sophisticated strategies represent natural extensions of CAPM's theoretical framework to new risk dimensions and market segments. Behavioural finance research has provided important insights into the psychological and institutional factors that can cause departures from CAPM's predictions whilst generally supporting the model's normative implications for rational investment behaviour. Understanding investor biases and market inefficiencies can help explain empirical anomalies in CAPM performance without necessarily invalidating the model's prescriptive value for rational portfolio construction. This research suggests that CAPM may be better understood as a normative model for how investors should behave rather than a positive model of how they actually do behave. Technology-enabled investment platforms and robo-advisors have made CAPM-inspired portfolio construction accessible to individual investors on an unprecedented scale. Modern portfolio allocation algorithms frequently employ CAPM principles to construct diversified portfolios whilst incorporating behavioural insights and practical constraints that acknowledge real-world implementation challenges. These applications demonstrate how CAPM's theoretical framework can be adapted to serve contemporary investment needs whilst maintaining its core emphasis on systematic risk management and diversification benefits. International capital market integration has created new opportunities for CAPM application whilst highlighting additional complexities related to currency risk, political risk, and market segmentation effects. Modern international portfolio management increasingly employs CAPM-inspired frameworks that incorporate these additional risk dimensions whilst maintaining the model's systematic approach to risk-return trade-offs. These applications demonstrate the flexibility and adaptability of CAPM's theoretical framework across different market contexts and investment environments. ConclusionThe Capital Asset Pricing Model stands as one of the most remarkable intellectual achievements in the history of financial economics, representing a rare convergence of theoretical elegance, practical applicability, and profound influence on both academic understanding and professional practice. Developed through the simultaneous efforts of four brilliant economists in the early 1960s, CAPM emerged from Harry Markowitz's foundation in modern portfolio theory to provide the first rigorous framework for understanding how systematic risk should be reflected in expected returns across capital markets. The model's mathematical simplicity—captured in the elegant linear relationship between expected return, beta, and market risk premium—belies its sophisticated theoretical underpinnings and revolutionary implications for investment management. William Sharpe's emergence as the primary architect of CAPM, culminating in his 1990 Nobel Prize recognition, exemplifies the profound impact that rigorous theoretical work can have on practical financial decision-making. Sharpe's journey from a disappointed graduate student seeking to inject mathematical rigour into financial practice to a Nobel laureate whose insights guide trillions of dollars in investment decisions demonstrates how academic research can fundamentally transform entire industries. His continued contributions to financial theory and practice, including the development of the Sharpe ratio and returns-based style analysis, illustrate the enduring value of the systematic approach to risk and return analysis that CAPM pioneered. The practical applications of CAPM have proven remarkably durable despite significant theoretical criticisms and empirical challenges. The model's influence on index fund development, regulatory frameworks, and institutional investment management reflects its fundamental insight that diversification represents the primary tool available to investors for managing risk whilst generating appropriate returns. The emergence of factor investing, smart beta strategies, and sophisticated risk management techniques represents evolutionary developments that build upon rather than replace CAPM's core theoretical framework, suggesting that the model's fundamental insights about systematic risk and market efficiency retain significant validity. The empirical challenges facing CAPM, including the size effect, value premium, and low-beta anomaly, have sparked productive theoretical developments that have enriched rather than undermined the field of financial economics. Multi-factor models, behavioural finance insights, and enhanced risk management techniques all represent attempts to address CAPM's limitations whilst preserving its analytical framework and practical utility. These developments demonstrate the healthy evolution of financial theory in response to empirical evidence whilst maintaining connection to the fundamental principles that CAPM established. Contemporary applications of CAPM in ESG investing, international portfolio management, and technology-enabled investment platforms demonstrate the model's continuing relevance in addressing modern investment challenges. The framework's flexibility in accommodating new risk factors and market developments suggests that CAPM's influence will persist as financial markets continue to evolve and become increasingly complex. The model's emphasis on systematic risk measurement and diversification benefits provides enduring principles that remain valuable regardless of specific market conditions or technological developments. The educational impact of CAPM cannot be overstated, as the model continues to provide the foundational framework through which students and professionals develop their understanding of risk and return relationships in financial markets. The model's mathematical tractability and intuitive appeal make it an ideal pedagogical tool whilst its practical applications ensure that theoretical understanding translates into professional competence. This educational legacy ensures that CAPM's insights will continue to influence new generations of investment professionals and academic researchers. Looking toward the future, CAPM's role in financial theory and practice seems likely to evolve rather than diminish, with the model serving as a benchmark against which more sophisticated approaches can be evaluated and compared. The continuing development of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data analytics in investment management provides new tools for implementing CAPM-inspired strategies whilst potentially identifying new systematic risk factors that the model's framework can accommodate. These technological developments may enhance rather than replace the systematic approach to risk and return analysis that CAPM pioneered. The regulatory and institutional frameworks that incorporate CAPM principles, including fiduciary standards and prudent investor guidelines, provide structural support for the model's continuing influence regardless of academic debates about its empirical performance. These institutional applications reflect the model's value as a systematic approach to investment decision-making that can be consistently applied and objectively evaluated, qualities that remain valuable in professional investment contexts even when more sophisticated models are available. The Capital Asset Pricing Model ultimately represents more than a mathematical formula or theoretical construct—it embodies a fundamental approach to thinking about investment decisions that emphasises systematic analysis, quantitative methods, and logical consistency. These methodological contributions may prove to be CAPM's most enduring legacy, providing a framework for rational investment decision-making that transcends specific model limitations or empirical challenges. As financial markets continue to evolve and new investment challenges emerge, the analytical approach pioneered by Sharpe, Treynor, Lintner, and Mossin will likely continue to guide both theoretical development and practical application in the ongoing quest to understand and manage the fundamental trade-offs between risk and return in capital markets.

|

| |

| |

Quote: Merton Miller - Nobel Laureate in Economics“I favour passive investing for most investors, because markets are amazingly successful devices for incorporating information into stock prices.” - Merton Miller - Nobel Laureate in EconomicsMerton Miller, Nobel Laureate in Economics, was a pivotal figure in the development of modern financial theory and a leading advocate for passive investing. The quote, “I favour passive investing for most investors, because markets are amazingly successful devices for incorporating information into stock prices,” encapsulates Miller’s lifelong commitment to highlighting the power and efficiency of financial markets. About Merton Miller Miller (1923–2000) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990, sharing the honour with Harry Markowitz and William Sharpe for ground-breaking work in the field of financial economics. His most influential contribution, alongside Franco Modigliani, was the Modigliani-Miller theorem—a foundational principle which rigorously proved that, under certain conditions, the value of a firm is unaffected by its capital structure. This theorem underpinned the belief that markets price information efficiently and forms an intellectual basis for the case for passive investing. Beyond his Nobel-winning research, Miller was renowned for his candid commentary on investing. He consistently argued that, while individual investors might believe they possess superior insights, markets—comprised of thousands of informed participants—collectively synthesise information so effectively that it becomes extremely difficult for any single investor to outperform the index after costs. As he famously quipped, “Everybody has some information. The function of the markets is to aggregate that information, evaluate it and get it incorporated into prices”. Context of the Quote The quote is a summation of decades of academic research and market observation. Miller, reflecting on the odds of outperforming the market, reasoned that for “most investors”, passive investing is the only rational route. He noted the steep costs of active management—not just fees, but the resources required to “dig up information no one else has yet”. For Miller, market prices reflected the best available information, making attempts to “pick winners” a game of chance rather than skill for the majority. This view gained substantial traction, especially as the academic tradition moved toward the concept of market efficiency. Miller warned pension fund managers that failing to allocate the majority of their portfolios to passive strategies—typically 70–80%, by his estimation—was not just suboptimal, but potentially a breach of fiduciary duty. Leading Theorists in Passive Investing and Market Efficiency The academic roots of passive investing run deep, with a lineage of Nobel Laureates and theorists who shaped the discipline:

Broader Context The shift towards passive investing is not merely theoretical but has reshaped global markets. Decades of empirical research confirm Miller’s central insight: most investors “might just as well buy a share of the whole market, which pools all the information, than delude themselves into thinking they know something the market doesn’t”. Despite periodic debate—such as whether passive investing could itself distort markets—the evidence and leading academic voices overwhelmingly endorse its primacy for the majority of investors. Key Themes

Summary Table: Leading Theorists in Passive Investing Merton Miller’s quote stands not as a passing remark, but as the distilled wisdom of a career devoted to understanding and proving the power of markets. It is a touchstone statement for a generation of investors and fiduciaries committed to evidence over speculation, and efficiency over expense.

|

| |

| |

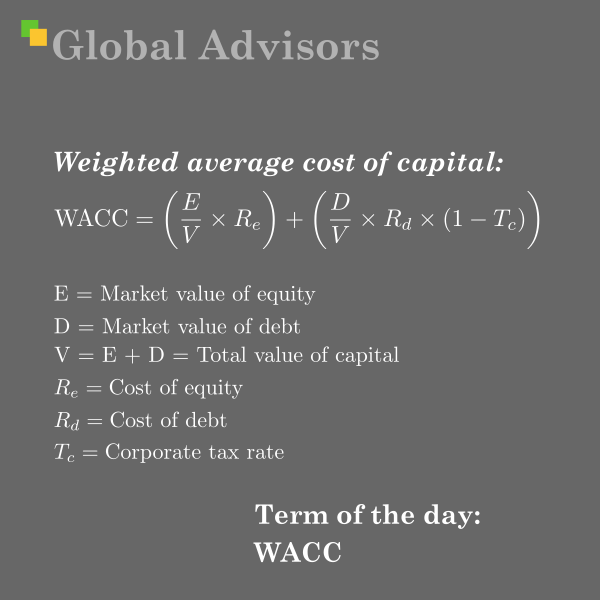

Term: Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) stands as one of the most fundamental and influential concepts in modern corporate finance, representing the blended cost of all capital sources a company employs to fund its operations and growth initiatives. This comprehensive metric, which integrates the costs of debt, equity, and preferred stock according to their proportional weights in a firm's capital structure, serves as a critical benchmark for investment decisions, corporate valuation, and strategic financial planning. The theoretical underpinnings of WACC trace back to the groundbreaking work of economists Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, whose capital structure propositions in the late 1950s revolutionised corporate finance theory and established the intellectual framework upon which WACC calculations are built. Their seminal research demonstrated that under certain idealised conditions, a firm's value remains independent of its capital structure, whilst also revealing how real-world factors such as taxation, bankruptcy costs, and information asymmetries create opportunities for optimal capital structure decisions that directly impact WACC calculations. Today, WACC functions not merely as an academic construct but as a practical tool employed by corporate executives, investment analysts, and strategic advisors to evaluate project feasibility, determine appropriate discount rates for discounted cash flow analyses, and assess the relative attractiveness of different financing strategies in an increasingly complex global financial landscape. Historical Context and Theoretical FoundationsThe conceptual foundation underlying WACC calculations emerged from a revolutionary period in academic finance during the mid-20th century, when traditional approaches to corporate finance were being fundamentally challenged by rigorous economic theory. Prior to this transformation, corporate finance decisions were often guided by rules of thumb and conventional wisdom rather than systematic theoretical frameworks. The landscape began to shift dramatically with the introduction of the Modigliani-Miller theorem, which provided the first comprehensive theoretical analysis of how capital structure decisions affect firm valuation. Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller's initial proposition, published in 1958, fundamentally challenged prevailing notions about optimal capital structure by demonstrating that under perfect market conditions—characterised by the absence of taxes, bankruptcy costs, agency costs, and asymmetric information—a firm's value remains entirely independent of its financing decisions. This seemingly counterintuitive finding suggested that whether a company funded its operations through debt, equity, or any combination thereof, its overall enterprise value would remain constant. The theorem's elegant mathematical proof relied on arbitrage arguments, showing that investors could replicate any corporate financing decision in their personal portfolios, thereby eliminating any potential value creation from capital structure choices. However, the true power of the Modigliani-Miller framework emerged not from its initial proposition but from its subsequent refinements that acknowledged real-world market imperfections. The second iteration of their work, incorporating corporate taxation, revealed that debt financing could indeed create value through the tax deductibility of interest payments. This insight established the theoretical basis for what would later become the interest tax shield component of WACC calculations, demonstrating that the after-tax cost of debt should be lower than its nominal cost due to the tax benefits associated with interest payments. The implications of this refined Modigliani-Miller theorem extended far beyond academic theory, establishing the intellectual groundwork for modern approaches to capital structure optimisation. By recognising that tax considerations create a genuine preference for debt financing—at least up to a certain point—the theorem provided the theoretical justification for the weighted average approach that characterises WACC calculations. The framework demonstrated that companies could potentially reduce their overall cost of capital by strategically balancing the tax advantages of debt against the increased financial risk and potential distress costs associated with higher leverage. This theoretical evolution coincided with broader developments in financial economics, including the emergence of portfolio theory and the capital asset pricing model, which provided sophisticated methods for estimating the cost of equity capital. These complementary theoretical advances created the comprehensive framework necessary for practical WACC calculations, combining insights about optimal capital structure with quantitative methods for determining the required returns on different types of capital. The convergence of these theoretical streams established WACC as both a conceptually sound and practically implementable tool for corporate financial decision-making. Components and Mathematical Framework of WACCThe calculation of WACC requires a sophisticated understanding of its constituent components, each of which presents unique challenges in terms of measurement and estimation. The fundamental WACC formula, expressed as WACC = (E/V × Re) + (D/V × Rd × (1 - Tc)), encapsulates the weighted contribution of each capital source to the firm's overall cost of capital. This deceptively simple equation masks considerable complexity in the determination of each component, requiring careful attention to market values, risk assessments, and tax considerations.

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the average rate a company must pay to all its capital providers—including both equity investors and lenders—weighted by the proportion each source represents in the firm's capital structure, and is commonly used as the discount rate in valuing investments and determining a business’s required rate of return.