| |

|

A daily bite-size selection of top business content.

PM edition. Issue number 1049

Latest 10 stories. Click the button for more.

|

| |

“Ultimately an investment is an instrument of trust as much as it is of belief. Every single part of your strategy is showing you're accountable and understand your responsibility with that. Take ownership.” - Henry Joseph-Grant - Just-Eat founder

Henry Joseph-Grant is widely recognised as a leading figure in the tech entrepreneurship and investment space. His career exemplifies the journey from humble beginnings to achieving major influence across international markets. Raised in Northern Ireland, Joseph-Grant’s academic pursuit in Arabic at the University of Westminster equipped him for the global business landscape, notably in his advisory work in Dubai. He began working early—starting as a paperboy at 11 and moving into various sales roles, before a pivotal tenure with Virgin.

His operational calibre was cemented by his contribution to scaling JUST EAT from its UK startup phase to its landmark IPO, which resulted in a £5.25bn market capitalisation. He subsequently founded The Entertainer in partnership with Abraaj Capital, and has held senior leadership roles (Director, VP, C-level) at disruptive technology firms.

Henry’s perspective is shaped by deep, hands-on engagement: navigating companies through crises, managing dramatic operational turnarounds, and leading restructuring efforts during economic shocks such as the pandemic. His experience includes acting as an angel investor, mentoring CEOs (at Seedcamp, Pitch@Palace, PiLabs) and judging major entrepreneur competitions including Richard Branson’s VOOM Pitch to Rich. Recognised among the top 25 UK entrepreneurs by Smith & Williamson, Henry is committed to fostering new generations of innovators and business leaders.

Context of the Quote

The quote captures Joseph-Grant’s core philosophy: in both entrepreneurship and investment, trust is as fundamental as belief or analytical conviction. Strategy is not simply a matter of tactics; it is a public demonstration of accountability and stewardship for others’ capital—be that from shareholders, employees, or the wider community. Trust is built through transparent, consistent ownership of outcomes, both positive and negative. This philosophy became especially salient in his leadership during industry crises, where he led teams through abrupt, challenging change, instilling a culture of responsibility and resilience.

Relevant Theorists and Thought Leaders

Joseph-Grant’s worldview aligns with and extends a body of thinking on trust, accountability, and stewardship within investment and leadership circles:

-

Peter L. Bernstein (1919-2009), author of "Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk", argued that all investment is a decision under uncertainty, underpinned by belief and the trustworthiness of those managing risk and capital. Bernstein traced the intellectual roots of taking and managing risk back to early insurance and probability theory, highlighting the psychological dimensions of trust inherent in capital allocation.

-

Warren Buffett, considered the most successful investor of the modern era, has consistently emphasised the interplay between trust, character, and performance in capital deployment. His letters to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders stress that he seeks partners and managers who will act as if all company actions are subject to public scrutiny—a direct echo of Joseph-Grant’s call for ownership and accountability.

-

Michael C. Jensen (emeritus professor, Harvard Business School) and William H. Meckling pioneered the concept of agency theory, which analyses the relationship between principals (investors) and agents (managers). Their analysis showed how trust and proper alignment of incentives are essential to guarding against opportunism and ensuring responsible stewardship.

-

Charles Handy, the UK management thinker, championed the “trust economy”, where intangible trust stocks often surpass formal contracts in their influence over business outcomes. Handy’s reflections on responsibility-through-action parallel Joseph-Grant’s insistence that strategy is not just a plan, but an ongoing display of stewardship.

-

Annette Mikes and Robert S. Kaplan (Harvard Business School) have explored risk leadership, demonstrating that trust is central to effective risk management; without authentic ownership from the top, frameworks fail.

Each of these theorists recognised that trust is not a soft attribute, but a measurable, actionable asset—and its absence carries material risk. Joseph-Grant’s phrasing highlights the imperative for every leader, founder, and investor: take ownership is not a cliché, but a competitive advantage and ethical responsibility.

Summary of Influence

The philosophy embedded in the quote is founded on Joseph-Grant’s lived experience, informed by crisis-tested leadership across markets and sectors. It reflects a broader intellectual tradition where trust, strategic clarity, and personal accountability are the cornerstones of sustainable investment and entrepreneurship. The challenge—and opportunity—posed is clear: in today’s interconnected, high-stakes environment, belief and trust are inseparable from value creation. Success follows when leaders are visibly accountable for the trust placed in them, at every level of the strategy.

|

| |

| |

|

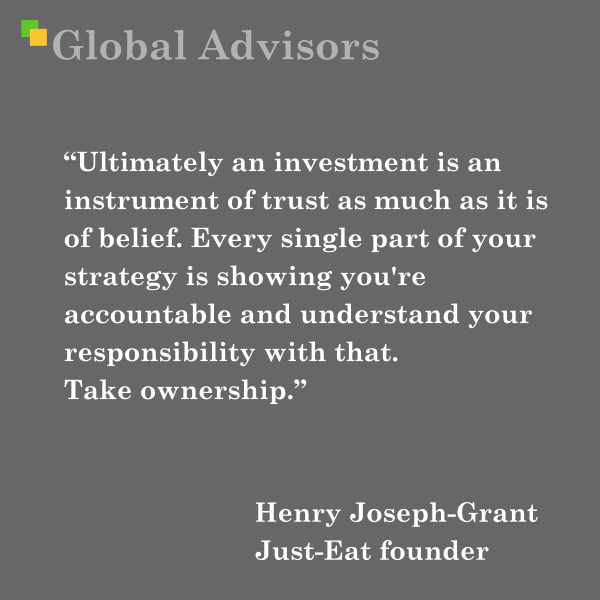

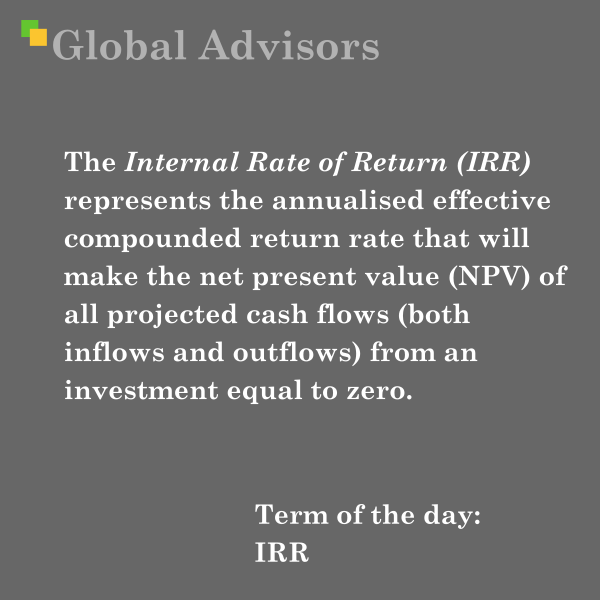

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a cornerstone metric in financial analysis, widely adopted in capital budgeting, private equity, real estate investment, and corporate strategy. IRR represents the annualised effective compounded return rate that will make the net present value (NPV) of all projected cash flows (both inflows and outflows) from an investment equal to zero. In essence, it is the discount rate at which the present value of projected cash inflows exactly balances the initial cash outlay and subsequent outflows.

Calculation and Application

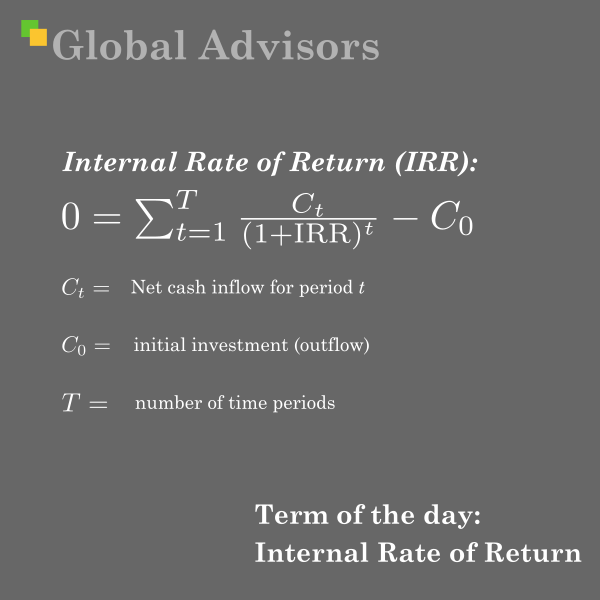

IRR is derived using the following equation:

Where:

- Ct = net cash inflow for period t

- Ct = initial investment (outflow)

-

- T = number of time periods

Analytical calculation of IRR is non-trivial (the formula is nonlinear in IRR), requiring iterative numerical methods or financial software to determine the rate that sets NPV to zero.

- IRR is expressed as a percentage and can be directly compared to a company’s cost of capital or required rate of return (RRR). An IRR exceeding these hurdles implies a financially attractive investment.

- IRR allows comparison across diverse investment opportunities and project types, using only projected cash flows and their timing. For instance, a higher IRR indicates a superior project, provided risks and other qualitative considerations are similar.

Role and Limitations

IRR incorporates the time value of money, recognising that early or larger cash flows enhance investment attractiveness. It is particularly suited to evaluating projects with well-defined, time-based cash flows, such as real estate developments, private equity funds, and corporate capital projects.

However, IRR also has notable limitations:

- If cash flows have complex sign changes, multiple IRRs can occur, complicating interpretation.

- IRR does not reflect scale — a small project may yield a high IRR but be insignificant in value.

- It assumes reinvestment of interim cash flows at the IRR, which may not be realistic in practice.

- IRR should be assessed alongside NPV, payback period, and scenario analysis to account for uncertainty in projections and limitations in model assumptions.

Strategic Context and Comparison

IRR is often used in conjunction with the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) and NPV in investment appraisal. While NPV provides the monetary value added, IRR offers a uniform rate metric useful for ranking projects.

Comparison to other measures:

- Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR): Unlike IRR, CAGR only considers start and end values, ignoring timing of intermediate flows.

- Return on Investment (ROI): ROI measures total percentage return but does not account for timing or annualisation as IRR does.

Key Takeaways

- IRR is the discount rate that equates the present value of future cash flows to the initial investment outlay (NPV = 0).

- It provides a basis for comparing investments and quantifying project attractiveness, especially when considering the timing and magnitude of returns.

- IRR should be interpreted within context, considering other financial metrics and qualitative factors.

Best Related Strategy Theorist: Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (1867–1947) is most closely associated with the conceptual foundations underlying IRR through his pioneering work in the theory of interest and investment decision making.

Backstory: Fisher’s Relationship to IRR

Fisher, an American economist and professor at Yale University, fundamentally reconceptualised how investors and firms should evaluate projects and capital investments. In his seminal works — notably The Rate of Interest (1907) and The Theory of Interest (1930) — Fisher introduced the principle that the rate of return on an investment should be evaluated as the discount rate at which the present value of expected future cash flows equals the current outlay. This approach constitutes the essence of IRR.

Fisher’s "investment criterion" – now known as the Fisher Separation Theorem – provided a theoretical justification for corporate investment decisions being made independently of individual preferences, guided solely by maximisation of present value. His analytical frameworks directly inform the calculation and interpretation of IRR and paved the way for subsequent developments in capital budgeting and financial theory.

Biography

-

- Academic Career: Fisher earned the first PhD in economics granted by Yale (1891), and remained a professor there throughout his life.

- Intellectual Contributions:

-

- Developed the theory of interest and capital budgeting, introducing concepts foundational to IRR.

- Pioneered the use of mathematical and statistical methods in economics.

- Recognised for Fisher’s Equation, connecting inflation, real, and nominal interest rates; a precursor to numerous modern finance tools.

- Influence: Fisher’s focus on discounting future cash flows and the time value of money made him a key figure not only in economics but also in finance. His ideas underpin many investment evaluation tools, including NPV and IRR, and have endured as best practice for investment professionals globally.

Fisher’s work bridges economic theory and practical strategy, making him the most authoritative figure associated with the conceptual foundations and strategic application of IRR.

Summary:

- IRR is the universal rate at which a project breaks even in NPV terms, holistically integrating the timing and magnitude of all cash flows.

- Irving Fisher’s theoretical developments directly underpin IRR’s use in modern financial strategy, establishing him as the most relevant strategy theorist for this concept.

|

| |

| |

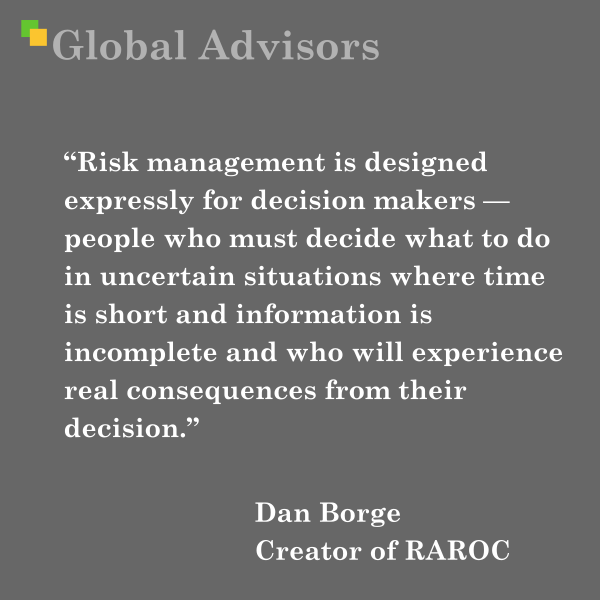

“Risk management is designed expressly for decision makers—people who must decide what to do in uncertain situations where time is short and information is incomplete and who will experience real consequences from their decision.” - Dan Borge - Creator of RAROC

Backstory and context of the quote

- Decision-first philosophy: The quote distils a core tenet of modern risk practice—risk management exists to improve choices under uncertainty, not to produce retrospective explanations. It aligns with the practical aims of RAROC: give managers a single, risk-sensitive yardstick to compare opportunities quickly and allocate scarce capital where it will earn the highest risk-adjusted return, even when information is incomplete and time-constrained.

- From accounting profit to economic value: Borge’s work formalised the shift from accounting measures (ROA, ROE) to economic profit by adjusting returns for expected loss and using economic capital as the denominator. This embeds forecasts of loss distributions and tail risk in pricing, limits and capital allocation—tools designed to influence the next decision rather than explain the last outcome.

- Institutional impact: The RAROC system was explicitly built to serve two purposes—risk management and performance evaluation—so decision makers can price risk, set hurdle rates, and steer portfolios in real time, consistent with the quote’s emphasis on consequential, time-bound choices.

Who is Dan Borge?

- Role and contribution: Dan Borge is widely credited as the principal designer of RAROC at Bankers Trust in the late 1970s, where he rose to senior managing director and head of strategic planning. RAROC became the template for risk-sensitive capital allocation and performance measurement across global finance.

- Career arc: Before banking, Borge was an aerospace engineer at Boeing; he later earned a PhD in finance from Harvard Business School and spent roughly two decades at Bankers Trust before becoming an author and consultant focused on strategy and risk management.

- Publications and influence: Borge authored The Book of Risk, translating quantitative risk methods into practical guidance for executives, reflecting the same “decision-under-uncertainty” ethos captured in the quote. His approach influenced internal economic-capital frameworks and, indirectly, the adoption of risk-based metrics aligned with regulatory capital thinking.

How the quote connects to RAROC—and its contrast with RORAC

- RAROC in one line: A risk-based profitability framework that measures risk-adjusted return per unit of economic capital, giving a consistent basis to compare businesses with different risk profiles.

- Why it serves decision makers: By embedding expected loss and holding capital for unexpected loss (often VaR-based) in a single metric, RAROC supports rapid, like-for-like choices on pricing, capital allocation, and portfolio mix in uncertain conditions—the situation Borge describes.

- RORAC vs RAROC: RORAC focuses the risk adjustment on the denominator by using risk-adjusted/allocated capital, often aligned to capital adequacy constructs; RAROC adjusts both sides, making the numerator explicitly risk-adjusted as well. RORAC is frequently an intermediate step toward the fuller risk-adjusted lens of RAROC in practice.

Leading theorists related to the subject

- Dan Borge (application architect): Operationalised enterprise risk management via RAROC, integrating credit, market, and operational risk into a coherent capital-allocation and performance system used for both risk control and strategic decision-making.

- Robert C. Merton and colleagues (contingent claims and risk-pricing foundations): Option-pricing and intermediation theory underpinned the quantification of risk and the translation of uncertainty into capital and pricing inputs later embedded in frameworks like RAROC. Their work provided the theoretical basis to model loss distributions and capital buffers that RAROC operationalises for decisions.

- Banking risk-management canon (economic capital and performance): The RAROC literature emphasises economic capital as a buffer for unexpected losses across credit, market, and operational risks, typically calculated with VaR methods—central elements that make risk-adjusted performance comparable and actionable for management teams.

Why the quote endures

- It defines the purpose of the function: Risk is not eliminated; it is priced, prioritised, and steered. RAROC operationalises this by tying risk-taking to economic value creation and solvency through a single decision metric, so leaders can act decisively when the clock is running and information is imperfect.

- Cultural signal: Framing risk management as a partner to strategy—not a historian of variance—has shaped how banks, insurers, and asset managers set hurdle rates, rebalance portfolios, and justify capital allocation to stakeholders under robust, forward-looking logic.

Selected biographical highlights of Dan Borge

- Aerospace engineer at Boeing; PhD in finance (Harvard); ~20 years at Bankers Trust; senior managing director and head of strategic planning; architect of RAROC; later author and consultant on risk and strategy.

- The Book of Risk communicates rigorous methods in accessible language, consistent with his focus on aiding real-world decisions under uncertainty.

- Recognition as principal architect of the first enterprise risk-management system (RAROC) at Bankers Trust, with enduring influence on risk-adjusted measurement and capital allocation in global finance.

|

| |

| |

|

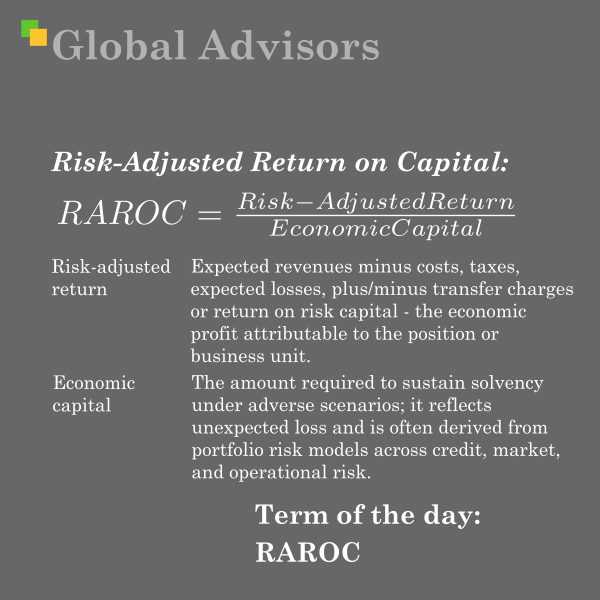

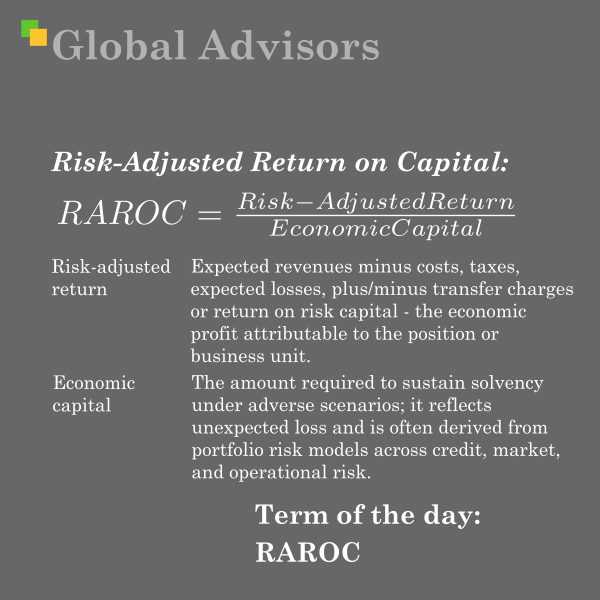

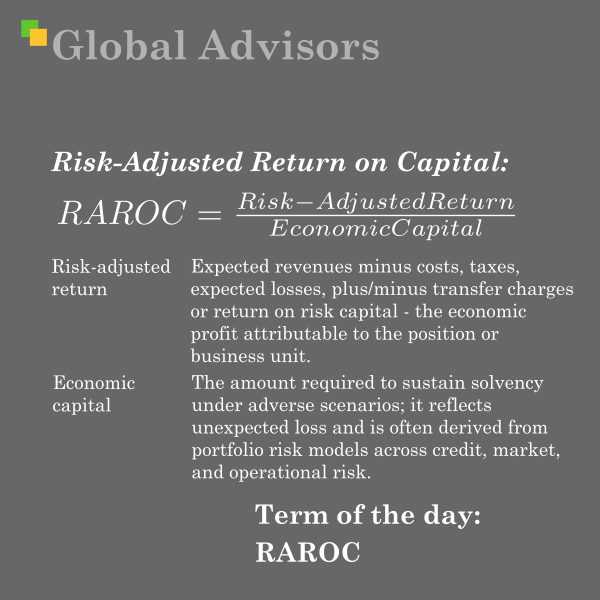

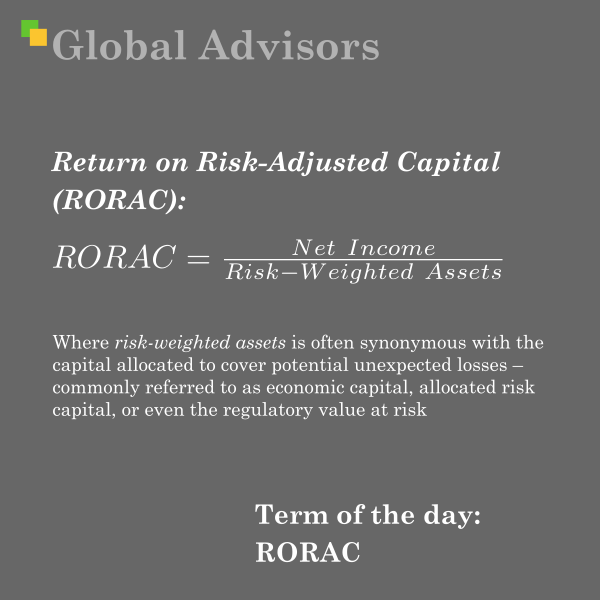

RAROC is a risk-based profitability framework that measures the risk-adjusted return earned per unit of economic capital, enabling like-for-like performance assessment, pricing, and capital allocation across activities with different risk profiles. Formally, RAROC equals risk-adjusted return (often after-tax, net of expected losses and other risk adjustments) divided by economic capital, where economic capital is the buffer held against unexpected loss across credit, market, and operational risk, commonly linked to VaR-based internal models:

Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC) measures the risk-adjusted return earned per unit of economic capital, enabling like-for-like performance assessment, pricing, and capital allocation across activities with different risk profiles.

Key components and calculation

- Numerator: risk-adjusted net income (e.g., expected revenues minus costs, taxes, expected losses, plus/minus transfer charges or return on risk capital), capturing the economic profit attributable to the position or business unit.

- Denominator: economic capital—the amount required to sustain solvency under adverse scenarios; it reflects unexpected loss and is often derived from portfolio risk models across credit, market, and operational risk.

- Decision rule: a unit creates value if its RAROC exceeds the cost of equity; this supports hurdle-rate setting and portfolio rebalancing.

What RAROC is used for

- Performance measurement: provides a consistent, risk-normalised basis to compare products, clients, and business lines with very different risk/return profiles.

- Capital allocation: guides allocation of scarce equity to activities with the highest risk-adjusted contribution, improving the bank’s economic capital structure.

- Pricing and limits: informs risk-based pricing, transfer pricing, and limit-setting by linking returns, expected loss, and required capital in one metric.

- Governance: integrates risk and finance by aligning business performance evaluation with the firm’s solvency objectives and risk appetite.

Contrast: RAROC vs RORAC

- Definition

- RAROC: risk-adjusted return on (economic) capital; adjusts the numerator for risk (e.g., expected losses and other risk charges) and uses economic capital in the denominator.

- RORAC: return on risk-adjusted capital; typically leaves the numerator closer to accounting net income minus expected losses, and focuses the adjustment on the denominator via allocated/risk-adjusted capital tied to capital adequacy principles (e.g., Basel).

- Practical distinction

- RAROC is the more “fully” risk-adjusted metric—both sides are risk-aware, making it suited to enterprise-wide pricing, capital budgeting, and stress-informed planning.

- RORAC is often an intermediate step that sharpens capital allocation by tailoring the denominator to risk, commonly used for business-unit benchmarking where the numerator is less extensively adjusted.

- Regulatory link

- RORAC usage has increased where capital adjustments are anchored to Basel capital adequacy constructs; RAROC remains the canonical internal economic-capital lens for value creation per unit of unexpected loss capacity.

Best related strategy theorist: Dan Borge

- Relationship to RAROC: Dan Borge is credited as the principal designer of the RAROC framework at Bankers Trust in the late 1970s, which became the template for risk-sensitive capital allocation and performance measurement across global banks.

- Rationale for selection: Because RAROC operationalises strategy through risk-based capital allocation—prioritising growth where risk-adjusted value is highest—Borge’s work sits at the intersection of corporate strategy, risk, and finance, shaping how institutions set hurdle rates, manage portfolios, and compete on disciplined risk pricing.

- Biography (concise): Borge’s role at Bankers Trust involved building an enterprise system that quantified economic capital across credit, market, and operational risks and linked it to pricing and performance; this institutionalised the two purposes of RAROC—risk management and performance evaluation—in mainstream banking practice.

How to use RAROC well (practitioner notes)

- Ensure coherent risk adjustments: align expected loss estimates, transfer pricing, and diversification effects with the economic capital model to avoid double counting or gaps.

- Compare to cost of equity and peers: use RAROC-minus-cost-of-equity spread as the decision compass for growth, remediation, or exit; incorporate benchmark RAROC bands by segment.

- Tie to stress and planning: reconcile business-as-usual RAROC with stressed capital needs so that pricing and allocation remain resilient when conditions deteriorate.

Definitions at a glance

- RAROC = after-tax risk-adjusted net income ÷ economic capital.

- Economic capital = capital held against unexpected loss across risk types; often VaR-based internally, distinct from accounting equity and regulatory minimums.

- RORAC = (net income minus expected losses) ÷ risk-adjusted/allocated capital; commonly aligned to Basel-style capital attribution at business-unit level.

|

| |

| |

“The purpose of risk management is to improve the future, not to explain the past.” - Dan Borge - Creator of RAROC

This line captures the pivot from retrospective control to forward-looking decision advantage that defined the modern risk discipline in banking. According to published profiles, Dan Borge was the principal architect of the first enterprise risk-management system, RAROC (Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital), developed at Bankers Trust in the late 1970s, where he served as head of strategic planning and as a senior managing director before becoming an author and consultant on strategy and risk management. His applied philosophy—set out in his book The Book of Risk and decades of practice—is that risk tools exist to shape choices, allocate scarce capital, and set prices commensurate with uncertainty so that institutions create value across cycles rather than merely rationalise outcomes after the fact.

Backstory and context of the quote

- Strategic intent over post-mortems: The quote distils the idea that risk management’s primary job is to enable better ex-ante choices—pricing, capital allocation, underwriting standards, and limits—so future outcomes improve in expected value and resilience. This is the logic behind RAROC, which evaluates opportunities on a common, risk-sensitive basis so managers can redeploy capital to the highest risk-adjusted uses.

- From accounting results to economic reality: Borge’s work shifted emphasis from accounting profit to economic profit by introducing economic capital as the denominator for performance measurement and by adjusting returns for expected losses and unhedged risks. This allows performance evaluation and risk control to be integrated, so decisions are guided by forward-looking loss distributions rather than historical averages alone.

- Institutional memory, not rear-view bias: Post-event analysis still matters, but in Borge’s framework it feeds model calibration and capital standards whose purpose is improved next-round decisions—credit selection, concentration limits, market risk hedging—rather than backward justification. This is consistent with the RAROC system’s twin purposes: risk management and performance evaluation.

- Communication and culture: As an executive and later as an author, Borge emphasised that risk is a necessary input to value creation, not merely a hazard to be minimised. His public biographies highlight a practitioner’s pedigree—engineer at Boeing, PhD in finance, two decades at Bankers Trust—grounding the quote in a career spent building tools that make organisations more adaptive to future uncertainty.

Who is Dan Borge?

- Career: Aerospace engineer at Boeing; PhD in finance from Harvard Business School; 20 years at Bankers Trust rising to senior managing director and head of strategic planning; principal architect of RAROC; subsequently an author and advisor on strategy and risk.

- Publications: Author of The Book of Risk, which translates quantitative risk concepts for executives and general readers and reflects his conviction that rigorous risk thinking should inform everyday decisions and corporate strategy.

- Lasting impact: RAROC became a standard for risk-sensitive capital allocation and pricing in global banking and influenced later regulatory and internal-capital frameworks that rely on economic capital as a buffer against unexpected losses across credit, market, and operational risks.

How the quote connects to RAROC and RORAC

- RAROC (Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital): Measures risk-adjusted performance by comparing expected, risk-adjusted return to the economic capital required as a buffer against unexpected loss; it provides a consistent yardstick across businesses with different risk profiles. This enables management to take better future decisions on where to grow, how to price, and what to hedge—precisely the “improve the future” mandate.

- RORAC (Return on Risk-Adjusted Capital): Uses risk-adjusted or allocated capital in the denominator but typically leaves the numerator closer to reported net income; it is often a practical intermediate step toward the full risk-adjusted measurement of RAROC and is referenced increasingly in contexts aligned with Basel capital concepts.

Leading theorists related to the subject

- Fischer Black, Myron Scholes, and Robert Merton: Their option-pricing breakthroughs and contingent-claims insights underpinned modern market risk measurement and hedging, enabling the pricing of uncertainty that RAROC-style frameworks depend on to translate risk into required capital and pricing.

- William F. Sharpe: The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) provided a foundational lens for relating expected return to systematic risk, an intellectual precursor to enterprise approaches that compare returns per unit of risk across activities.

- Dan Borge: As principal designer of RAROC at Bankers Trust, he operationalised these theoretical advances into a bank-wide system for allocating economic capital and evaluating performance, embedding risk in everyday management decisions.

Why it matters today

- Enterprise decisions under uncertainty: The move from explaining past volatility to shaping future outcomes remains central to capital planning, stress testing, and strategic allocation. RAROC-style thinking continues to inform how institutions set hurdle rates, manage concentrations, and price products across credit, market, and operational risk domains.

- Cultural anchor: The quote serves as a reminder that risk functions add the most value when they are partners in strategy—designing choices that raise long-run risk-adjusted returns—rather than historians of failure. That ethos traces directly to Borge’s contribution: risk as a discipline for better choices ahead, not merely better stories behind.

|

| |

| |

|

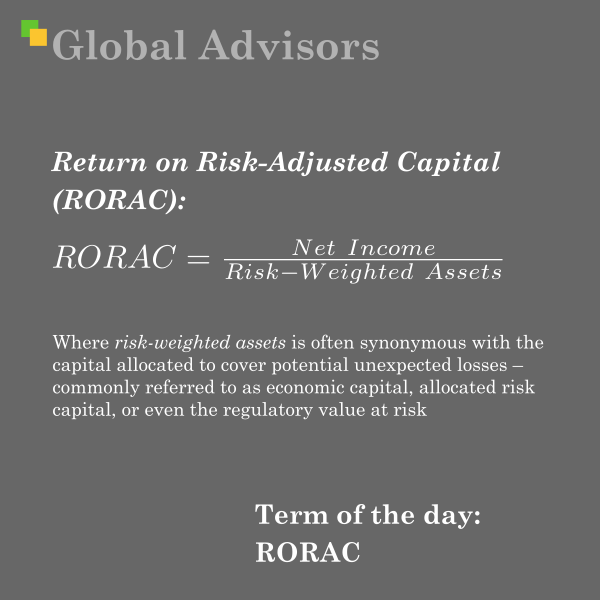

Return on Risk-Adjusted Capital (RORAC) is a financial performance metric that evaluates the profitability of a project, business unit, or company by relating net income to the amount of capital at risk, where that capital has been specifically adjusted to account for the risks inherent in the activity under review. It enables a direct comparison of returns between different business units, projects, or products that may carry differing risk profiles, allowing for a more precise assessment of economic value creation within risk management frameworks.

Formula for RORAC:

Return on Risk-Adjusted Capital (RORAC) evaluates the profitability of a project, business unit, or company by relating net income to the amount of capital at risk, where that capital has been specifically adjusted to account for the risks inherent in the activity under review.

Where risk-weighted assets are often synonymous with the capital allocated to cover potential unexpected losses – commonly referred to as economic capital, allocated risk capital, or even the regulatory value at risk. Unlike Return on Equity (ROE), which uses the company’s entire equity base, RORAC employs a denominator that adjusts for the riskiness of specific lines of business or transactions.

By allocating capital in proportion to risk, RORAC supports:

- Risk-based pricing at the granular (e.g. product or client) level

- Comparability across divisions with different risk exposures

- More effective performance measurement, especially in financial institutions where capital allocation is a critical management decision.

Contrast: RORAC vs. RAROC

RORAC is a step beyond traditional metrics (like ROE) by recognising different risk profiles in how much capital is assigned, but does not fully risk-adjust the numerator. RAROC, by contrast, also incorporates provisions for expected losses and other direct adjustments to profitability, providing a purer view of economic value generation given all forms of risk.

Best Related Strategy Theorist: Dan Borge

Biography and Relevance:

Dan Borge is widely credited as the architect of RAROC, making him instrumental to both RAROC and, by extension, RORAC. In the late 1970s, while at Bankers Trust, Borge led a project to develop a more rigorous framework for risk management and capital allocation in banking. The resulting RAROC framework was revolutionary: it introduced a risk-sensitive approach to capital allocation, integrating credit risk, market risk, and operational risk into a unified model for measuring financial performance.

Borge’s contributions include:

- Establishing RAROC as a foundational risk management principle for global banks, influencing regulatory frameworks such as the Basel Accords.

- Advocating the principle that performance measurement should reflect not just raw returns but also the economic capital required as a buffer against potential losses.

Though Borge is not explicitly associated with RORAC by name, RORAC is widely recognised as an extension or adaptation of the principles he introduced – focusing especially on the risk-based allocation of capital for more effective resource deployment and incentive alignment.

Legacy in Strategy:

Dan Borge’s work laid the groundwork for risk-based performance management in financial institutions, making metrics such as RORAC and RAROC central to how banks, insurers, and investment firms manage risk and measure profitability today. His theories underpin much of contemporary capital allocation, risk pricing, and value-based management in these sectors.

Summary of Key Points:

- RORAC measures return based on risk-adjusted capital and is a bridge between ROE and fully risk-adjusted performance metrics like RAROC.

- RAROC adjusts both return and capital for risk, offering a more comprehensive risk/performance measure and forming the foundation of modern risk-sensitive management.

- Dan Borge is the most relevant theorist, having originated RAROC at Bankers Trust, and his legacy continues to influence the theory and application of RORAC.

|

| |

| |

“Knowledge-building proficiency involves constructive skepticism about what we think we know. Our initial perceptions of problems and initial ideas for new products can be hindered by assumptions that are no longer valid but rarely questioned.” - Bartley J. Madden - Value creation leader

Bartley J. Madden’s work is anchored in the belief that true progress—whether in business, investment, or society—depends on how proficiently we build, challenge, and revise our knowledge. The featured quote reflects decades of Madden’s inquiry into why firms succeed or fail at innovation and long-term value creation. In his view, organisations routinely fall victim to unexamined assumptions: patterns of thinking that may have driven past success, but become liabilities when environments change. Madden calls for a “constructive skepticism” that continuously tests what we think we know, identifying outdated mental models before they erode opportunity and performance.

Bartley J. Madden: Life and Thought

Bartley J. Madden is a leading voice in strategic finance, systems thinking, and knowledge-building practice. With a mechanical engineering degree earned from California Polytechnic State University in 1965 and an MBA from UC Berkeley, Madden’s early career took him from weapons research in the U.S. Army into the world of investment analysis. His pivotal transition came in the late 1960s, when he co-founded Callard Madden & Associates, followed by his instrumental role in developing the CFROI (Cash Flow Return on Investment) framework at Holt Value Associates—a tool now standard in evaluating corporate performance and capital allocation in global markets.

Madden’s career is marked by a restless, multidisciplinary curiosity: he draws insights from engineering, cognitive psychology, philosophy, and management science. His research increasingly focused on what he termed the “knowledge-building loop” and systems thinking—a way of seeing complex business problems as networks of interconnected causes, feedback loops, and evolving assumptions, rather than linear chains of events. In both his financial and philanthropic work, including his eponymous Madden Center for Value Creation, Madden advocates for knowledge-building cultures that empower employees to challenge inherited beliefs and to experiment boldly, seeing errors as opportunities for learning rather than threats.

His books—such as Value Creation Principles, Reconstructing Your Worldview, and My Value Creation Journey—emphasise systems thinking, the importance of language in shaping perception, and the need for leaders to ask better questions. Madden directly credits thinkers such as John Dewey for inspiring his conviction in inquiry-driven learning and Adelbert Ames Jr. for insights into the pitfalls of perception and assumption.

Intellectual Backstory and Related Theorists

Madden’s views develop within a distinguished lineage of scholars dedicated to organisational learning, systems theory, and the dynamics of innovation. Several stand out:

- John Dewey (1859–1952): The American pragmatist philosopher deeply influenced Madden’s sense that expertise must continuously be updated through critical inquiry and experimentation, rather than resting on tradition or authority. Dewey championed a scientific, reflective approach to practical problem-solving that resonates throughout Madden’s work.

- Adelbert Ames Jr. (1880–1955): A pioneer of perceptual psychology, Ames’ experiments revealed how easily human perceptions are deceived by context and previous experience. Madden draws on Ames to illustrate how even well-meaning business leaders can be misled by outmoded assumptions.

- Russell Ackoff (1919–2009): One of the principal architects of systems thinking in management, Ackoff insisted that addressing problems in isolation leads to costly errors—a foundational idea in Madden’s argument for holistic knowledge-building.

- Peter Senge: Celebrated for popularising the “learning organisation” and systems thinking through The Fifth Discipline, Senge’s influence underpins Madden’s practical prescriptions for continuous learning and the breakdown of organisational silos.

- Karl Popper (1902–1994): Philosopher of science, Popper argued that the pursuit of knowledge advances through critical testing and falsifiability. Madden’s constructive scepticism echoes Popper’s principle that no idea should be immune from challenge if progress is to be sustained.

Application and Impact

Madden’s philosophy is both a warning and a blueprint. The tendency of individuals and organisations to become trapped by their own outdated assumptions is a perennial threat. By embracing systems thinking and prioritising open, critical inquiry, businesses can build resilient cultures capable of adapting to change—creating sustained value for all stakeholders.

In summary, the context of Madden’s quote is not merely a call to think differently, but a rigorous, practical manifesto for the modern organisation: challenge what you think you know, foster debate over dogma, and place knowledge-building at the core of value creation.

|

| |

| |

|

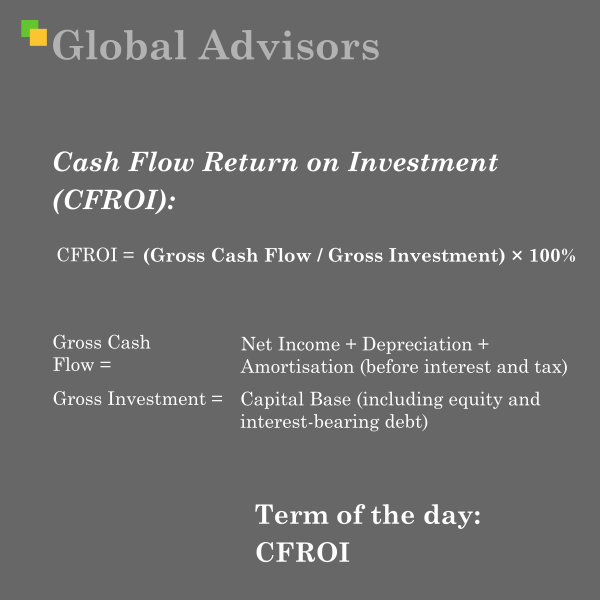

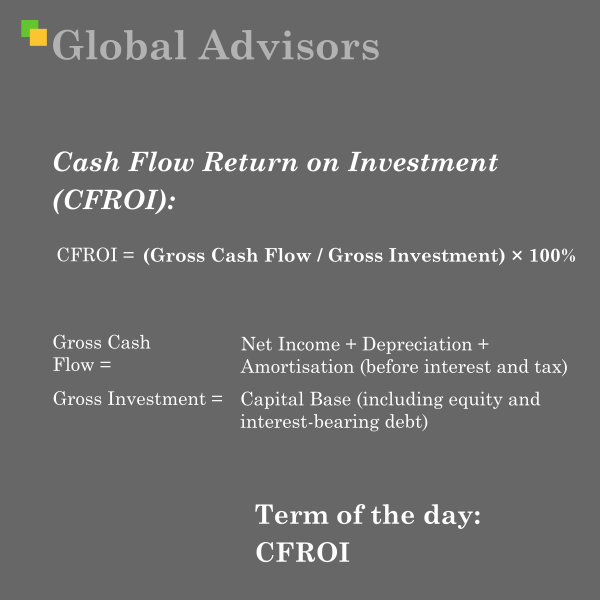

CFROI (Cash Flow Return on Investment) is a financial performance metric designed to assess how efficiently a company generates cash returns from its invested capital, providing a clear measure of real profitability that goes beyond traditional accounting-based ratios like Return on Equity (ROE) or Return on Assets (ROA).

CFROI calculates the cash yield on capital by focusing on the cash generated from business operations—before interest and taxes—relative to the total capital invested (including both equity and interest-bearing debt). This approach offers critical advantages:

- Focus on cash flow: By using cash flow rather than accounting earnings, CFROI presents a clearer picture of underlying economic value, especially where accounting rules may obscure true profitability.

- Neutralises accounting differences: CFROI can act as a universal yardstick that limits the impact of different accounting standards, depreciation methods, or tax regimes, making cross-company and cross-border comparisons more meaningful.

- Adjusts for capital costs and asset life: The measure reflects asset depreciation and shifts in the cost of capital, making it particularly useful for businesses with large, long-term investments.

- Investor-centric perspective: CFROI’s explicit connection to internal rate of return (IRR) means it is widely adopted by equity analysts, fund managers, and corporate strategists to evaluate both individual companies and wider markets, as well as to benchmark performance, identify undervalued companies, and inform investment decisions.

The standard formula for CFROI is:

CFROI = (Gross Cash Flow / Gross Investment) × 100%

- Gross Cash Flow is typically calculated as net income plus non-cash expenses (depreciation, amortisation), before interest and tax.

- Gross Investment includes all capital invested, both equity and debt.

Calculation notes

Gross Cash Flow

Gross Cash Flow = Net Income + Depreciation + Amortisation (before interest and tax)

Notes:

- Some practitioners define Gross Cash Flow as EBIT plus non-cash charges: Gross Cash Flow = EBIT + Depreciation + Amortisation

- If you prefer a pre-tax cash-flow view, use: Gross Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow before interest and tax + Non-cash charges

Gross Investment

Gross Investment = Capital Base (including equity and interest-bearing debt)

Interpretation

CFROI > Cost of Capital implies value creation

CFROI < Cost of Capital implies value destruction

Founding Strategy Theorist and Historical Background

The development of Cash Flow Return on Investment (CFROI) originated from the work of Holt Value Associates, a consultancy established by Bob Hendricks, Eric Olsen, Marvin Lipson, and Rawley Thomas in the 1980s. CFROI was created to address the deficiencies of traditional accounting ratios and valuation metrics by focusing on a company's actual cash generation and capital allocation decisions. The methodology treats each company as an investment project, evaluating the streams of cash flows generated by its assets over their productive life, adjusted for inflation and capital costs. This approach enables effective cross-company and cross-industry comparisons, providing a clearer insight into economic value creation versus destruction.

CFROI rapidly gained adoption among institutional investors and corporates, offering a more accurate reflection of economic profitability than standard accounting measures, and laid the groundwork for broader value-based management practices. The metric continues to underpin performance evaluation systems for leading investment houses and strategic advisory firms, serving as a cornerstone for analysing long-term value creation in corporate finance and portfolio management.

CFROI (Cash Flow Return on Investment) is a financial performance metric designed to assess how efficiently a company generates cash returns from its invested capital, providing a clear measure of real profitability that goes beyond traditional accounting-based ratios like Return on Equity (ROE) or Return on Assets (ROA).

|

| |

| |

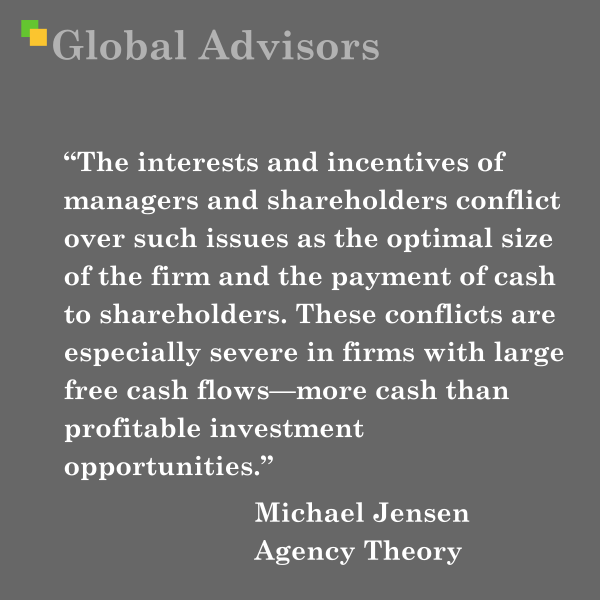

“The interests and incentives of managers and shareholders conflict over such issues as the optimal size of the firm and the payment of cash to shareholders. These conflicts are especially severe in firms with large free cash flows—more cash than profitable investment opportunities.” - Michael Jensen - “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers”

This work profoundly shifted our understanding of corporate finance and governance by introducing the concept of free cash flow as a double-edged sword: a sign of a firm’s potential strength, but also a source of internal conflict and inefficiency.

Jensen’s insight was to frame the relationship between corporate management (agents) and shareholders (principals) as inherently conflicted, especially when firms generate substantial cash beyond what they can profitably reinvest. In such cases, managers — acting in their own interests — may prefer to expand the firm’s size, prestige, or personal security rather than return excess funds to shareholders. This can lead to overinvestment, value-destroying acquisitions, and inefficiencies that reduce shareholder wealth.

Jensen argued that these “agency costs” become most acute when a company holds large free cash flows with limited attractive investment opportunities. Understanding and controlling the use of this surplus cash is, therefore, central to corporate governance, capital structure decisions, and the market for corporate control. He further advanced that mechanisms such as debt financing, share buybacks, and vigilant board oversight were required to align managerial behaviour with shareholder interests and mitigate these costs.

Michael C. Jensen – Biography and Authority

Michael C. Jensen (born 1939) is an American economist whose work has reshaped the fields of corporate finance, organisational theory, and governance. He is renowned for co-founding agency theory, which examines conflicts between owners and managers, and for developing the “free cash flow hypothesis,” now a core part of the strategic finance playbook.

Jensen’s academic career spanned appointments at leading institutions, including Harvard Business School. His early collaboration with William Meckling produced the foundational 1976 paper “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure”, formalising the costs incurred when managers’ interests diverge from those of owners. Subsequent works, especially his 1986 American Economic Review piece on free cash flow, have defined how both scholars and practitioners think about the discipline of management, boardroom priorities, dividend policy, and the rationale behind leveraged buyouts and takeovers.

Jensen’s framework links the language of finance with the realities of human behaviour inside organisations, providing both a diagnostic for governance failures and a toolkit for effective capital allocation. His ideas remain integral to the world’s leading advisory, investment, and academic institutions.

Related Leading Theorists and Intellectual Development

-

William H. Meckling

Jensen’s chief collaborator and co-author of the seminal agency theory paper, Meckling’s work with Jensen laid the groundwork for understanding how ownership structure, debt, and managerial incentives interact. Agency theory provided the language and logic that underpins Jensen’s later work on free cash flow.

-

Eugene F. Fama

Fama, a key contributor to efficient market theory and empirical corporate finance, worked closely with Jensen to explain how markets and boards provide checks on managerial behaviour. Their joint work on the role of boards and the market for corporate control complements the agency cost framework.

-

Michael C. Jensen, William Meckling, and Agency Theory

Together, they established the core problems of principal-agent relationships — questions fundamental not just in corporate finance, but across fields concerned with incentives and contracting. Their insights drive the modern emphasis on structuring executive compensation, dividend policy, and corporate governance to counteract managerial self-interest.

-

Richard Roll and Henry G. Manne

These theorists expanded on the market for corporate control, examining how takeovers and shareholder activism can serve as market-based remedies for agency costs and inefficient cash deployment.

Strategic Impact

These theoretical advances created the intellectual foundation for practical innovations such as leveraged buyouts, more activist board involvement, value-based management, and the design of performance-related pay. Today, the discipline around free cash flow is central to effective capital allocation, risk management, and the broader field of corporate strategy — and remains immediately relevant in an environment where deployment of capital is a defining test of leadership and organisation value.

|

| |

| |

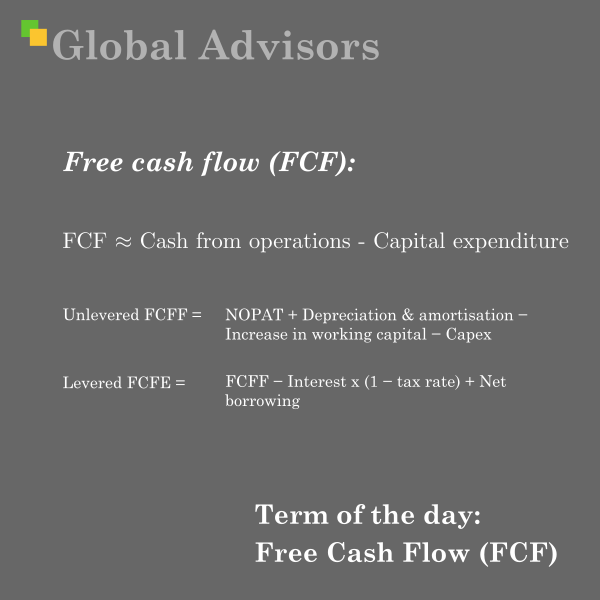

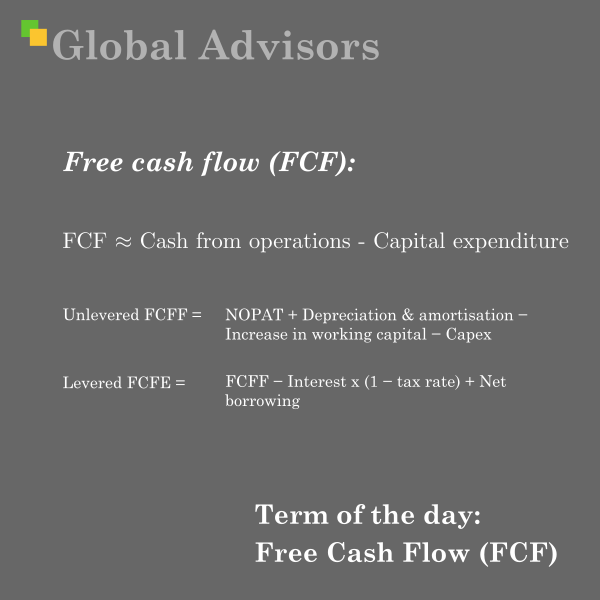

Definition and purpose

- Free cash flow (FCF) is the cash a company generates from its operations after it has paid the operating expenses and made the investments required to maintain and grow its asset base. It represents cash available to the providers of capital — equity and debt — for distribution, reinvestment, debt repayment or other corporate uses, without impairing the firm’s ongoing operations.

- Conceptually, FCF is the most direct indicator of a firm’s ability to fund dividends, share buy-backs, debt service and acquisitions from internal resources rather than external financing.

Common formulations

- Operating cash flow approach (practical):

FCF ~ Cash from operations - Capital expenditure (capex)

- Unlevered (to all capital providers) (accounting/valuation form):

FCFF = NOPAT + Depreciation & amortisation - Increase in working capital - Capex

where NOPAT = Net operating profit after tax

- Levered (to equity holders after debt payments):

FCFE = FCFF - Interest x (1 - tax rate) + Net borrowing

How it is used (strategic and financial)

- Valuation: FCF is the basis for discounted cash flow (DCF) models; projected FCFs discounted at an appropriate weighted average cost of capital (WACC) produce enterprise value.

- Capital allocation: Management uses FCF to decide between reinvestment, acquisitions, dividends, buy-backs or debt reduction.

- Financial health and liquidity: Positive and growing FCF signals the capacity to withstand shocks and pursue strategic options; persistent negative FCF may indicate structural issues or growth investment.

- Corporate governance and strategy: FCF levels influence managerial incentives, capital structure decisions and vulnerability to takeovers.

Drivers and determinants

- Revenue growth and margin profile (affects NOPAT)

- Working capital management (inventory, receivables, payables)

- Capital intensity — required capex for maintenance and growth

- Depreciation policy and tax regime

- Financing decisions (interest and net borrowing affect FCFE)

Common adjustments and measurement issues

- Distinguish maintenance capex from growth capex where possible — one is required to sustain operations, the other to expand them.

- Normalise one-off items (asset sales, litigation receipts, restructuring charges).

- Use consistent definitions across periods and peers when benchmarking.

- Beware that accounting earnings can diverge materially from cash flows; always reconcile net income with cash flow statements.

Strategic implications and typical responses

- High and stable FCF: allows strategic optionality — M&A, sustained dividends, share repurchases, or investment in R&D/innovation.

- Excess FCF with weak internal investment opportunities (the “free cash flow problem”): risk of managerial empire-building or wasteful spending; effective governance is required to ensure value-creating uses.

- Negative FCF during growth phases: may be acceptable if returns on invested capital justify external funding; however, persistent negative FCF with poor returns is a red flag.

Pitfalls and limitations

- FCF alone does not capture cost of capital or opportunity cost of investments; it must be evaluated in a valuation or strategic context.

- Short-term FCF optimisation can undermine long-term value (underinvestment in maintenance, R&D).

- Industry and lifecycle differences matter: capital-intensive or high-growth businesses naturally have very different FCF profiles.

Practical check list for executives and boards

- Reconcile reported FCF with sustainable maintenance requirements and strategic growth plans.

- Tie capital allocation policy to explicit hurdle rates and periodic capital review.

- Monitor trends in working capital and capex intensity as early indicators of operational change.

- Align executive incentives to value-creating uses of FCF and robust governance mechanisms.

Recommended quick example

- Company reports cash from operations of £200m and capex of £75m in a year:

FCF ~ £200m - £75m = £125m available for distribution or strategic use.

Most closely associated strategy theorist — Michael C. Jensen

Why he is the most relevant

- Michael C. Jensen is the scholar most closely associated with the theoretical treatment of free cash flow in corporate strategy and governance. He set out the “free cash flow hypothesis”, which links excess free cash flow to agency costs and managerial behaviour. His work frames how boards, investors and advisers approach capital allocation, payouts and takeover defence in the presence of substantial internal cash generation.

Backstory and relationship of his ideas to FCF

- Jensen’s contribution builds on agency theory: when managers control resources owned by shareholders, their objectives can diverge from those of owners. He argued that when firms generate significant free cash flow and lack profitable investment opportunities, managers face incentives to deploy that cash in ways that increase the size or prestige of the firm (empire-building) rather than shareholder value — for example, through low-value acquisitions, overstaffing, or excessive perquisites.

- To mitigate these agency costs, Jensen proposed mechanisms that reduce discretionary free cash flow or align managerial incentives with shareholder interests. The main remedies he identified include: increased dividend payouts or share repurchases (directing cash to owners), higher leverage (forcing interest and principal payments), active market for corporate control (takeovers discipline managers), and better executive compensation and governance structures.

- Jensen’s framing made free cash flow a strategic variable: it is not just a measure of liquidity but a determinant of governance risk, takeover vulnerability and the appropriate capital allocation framework.

Biography — concise professional profile

- Michael C. Jensen is an influential American economist and professor recognised for foundational work in agency theory, corporate finance and organisational economics. He rose to prominence through a series of widely cited papers that reshaped how academics and practitioners view managerial incentives, ownership structure and the governance of corporations.

- Key intellectual milestones:

- Seminal early work on agency theory with William Meckling, which formalised the costs arising when ownership and control are separated and remains central to corporate finance.

- Development of the free cash flow hypothesis, which articulated the link between excess cash, managerial incentives and takeover markets.

- Roles and influence:

- Held senior academic posts and taught at leading business schools, influencing generations of scholars and corporate leaders.

- Served as adviser to boards, institutional investors and practitioners, translating academic insights into governance reform and corporate strategy.

- His ideas have influenced policy debates on executive compensation, dividend policy and the role of debt in corporate discipline.

- Legacy and criticisms:

- Jensen’s work stimulated a large empirical and theoretical literature. Some later research nuance and moderate his claims: excess cash can fund innovation and strategic flexibility, and the relationship between FCF and bad managerial behaviour depends on governance context, industry dynamics and opportunity sets.

- Nonetheless, his framework remains a cornerstone for diagnosing the risks and governance trade-offs associated with free cash flow.

Further reading (core works)

- Jensen, M. C. — “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure” (co-authored with W. Meckling) — foundational for agency theory.

- Jensen, M. C. — article introducing the free cash flow perspective on corporate finance and takeovers.

Concluding strategic note

- Free cash flow deserves to be treated as a strategic indicator, not merely an accounting outcome. Jensen’s insights make it clear that the level and predictability of FCF should shape capital structure, governance arrangements and the firm’s approach to dividends, buy-backs and M&A. Boards should therefore link FCF forecasting to explicit capital allocation rules and governance safeguards to preserve long?-term shareholder value.

Free cash flow (FCF) is the cash a company generates from its operations after it has paid the operating expenses and made the investments required to maintain and grow its asset base. It represents cash available to the providers of capital — equity and debt — for distribution, reinvestment, debt repayment or other corporate uses, without impairing the firm’s ongoing operations.

|

| |

|