Our Johannesburg office rooms are named after thought leaders who have influenced our industry, our thinking and reflect our differentiation.

The Black room – named after Professor Fischer Black

Fischer Sheffey Black (January 11, 1938 – August 30, 1995) was an American economist, best known as one of the authors of the famous Black–Scholes equation.

Fischer Sheffey Black (January 11, 1938 – August 30, 1995) was an American economist, best known as one of the authors of the famous Black–Scholes equation.

The Nobel Prize is not given posthumously, so it was not awarded to Black in 1997 when his co-author Myron Scholes received the honor for their landmark work on option pricing along with Robert C. Merton, another pioneer in the development of valuation of stock options. In the announcement of the award that year, the Nobel committee prominently mentioned Black’s key role.

Black has also received recognition as the co-author of the Black–Derman–Toy interest rate derivatives model, which was developed for in-house use by Goldman Sachs in the 1980s but eventually published. He also co-authored the Black-Litterman model on global asset allocation while at Goldman Sachs.

The Advisory Board of The Journal of Performance Measurement inducted Black into the Performance & Risk Measurement Hall of Fame in 2017. The announcement appears in the Winter 2016/2017 issue of the journal. The Hall of Fame recognizes individuals who have made significant contributions to investment performance and risk measurement.

In 1973, Black, along with Myron Scholes, published the paper ‘The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities’ in ‘The Journal of Political Economy’. This was his most famous work and included the Black–Scholes equation.

In March 1976, Black proposed that human capital and business have “ups and downs that are largely unpredictable […] because of basic uncertainty about what people will want in the future and about what the economy will be able to produce in the future. If future tastes and technology were known, profits and wages would grow smoothly and surely over time.” A boom is a period when technology matches well with demand. A bust is a period of mismatch. This view made Black an early contributor to real business cycle theory.

It can be shown that the mathematical techniques developed in the option theory can be extended to provide a mathematical analysis of monetary theory and business cycles as well.

Black developed another version of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), called Black CAPM or zero-beta CAPM, that does not assume the existence of a riskless asset. This version was more robust against empirical testing and was influential in the widespread adoption of the CAPM.

Source: Wikipedia

The Coase touch-down room – named after Professor Ronald Coase

Ronald Harry Coase ( 29 December 1910 – 2 September 2013) was a British economist and author. He was for much of his life the Clifton R. Musser Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Chicago Law School, where he arrived in 1964 and remained for the rest of his life. After studying with the University of London External Programme in 1927–29, Coase entered the London School of Economics, where he took courses with Arnold Plant.

29 December 1910 – 2 September 2013) was a British economist and author. He was for much of his life the Clifton R. Musser Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Chicago Law School, where he arrived in 1964 and remained for the rest of his life. After studying with the University of London External Programme in 1927–29, Coase entered the London School of Economics, where he took courses with Arnold Plant.

Coase, who believed economists should study real markets and not theoretical ones, established the case for the corporation as a means to pay the costs of operating a marketplace. Coase is best known for two articles in particular: “The Nature of the Firm” (1937), which introduces the concept of transaction costs to explain the nature and limits of firms, and “The Problem of Social Cost” (1960), which suggests that well-defined property rights could overcome the problems of externalities (see Coase theorem). Additionally, Coase’s transaction costs approach is currently influential in modern organizational economics, where it was reintroduced by Oliver E. Williamson.

In The Nature of the Firm (1937) – a brief but highly influential essay – Coase attempts to explain why the economy features a number of business firms instead of consisting exclusively of a multitude of independent, self-employed people who contract with one another. Given that “production could be carried on without any organization [that is, firms] at all”, Coase asks, why and under what conditions should we expect firms to emerge?

Since modern firms can only emerge when an entrepreneur of some sort begins to hire people, Coase’s analysis proceeds by considering the conditions under which it makes sense for an entrepreneur to seek hired help instead of contracting out for some particular task.

The traditional economic theory of the time (in the tradition of Adam Smith) suggested that, because the market is “efficient” (that is, those who are best at providing each good or service most cheaply are already doing so), it should always be cheaper to contract out than to hire.

Coase noted, however, a number of transaction costs involved in using the market; the cost of obtaining a good or service via the market actually exceeds the price of the good. Other costs, including search and information costs, bargaining costs, keeping trade secrets, and policing and enforcement costs, can all potentially add to the cost of procuring something from another party. This suggests that firms will arise which can internalise the production of goods and services required to deliver a product, thus avoiding these costs. This argument sets the stage for the later contributions by Oliver Williamson: markets and hierarchies are alternative co-ordination mechanisms for economic transactions.

There is a natural limit to what a firm can produce internally, however. Coase notices “decreasing returns to the entrepreneur function”, including increasing overhead costs and increasing propensity for an overwhelmed manager to make mistakes in resource allocation. These factors become countervailing costs to the use of the firm.

Coase argues that the size of a firm (as measured by how many contractual relations are “internal” to the firm and how many “external”) is a result of finding an optimal balance between the competing tendencies of the costs outlined above. In general, making the firm larger will initially be advantageous, but the decreasing returns indicated above will eventually kick in, preventing the firm from growing indefinitely.

Other things being equal, therefore, a firm will tend to be larger:

- the lower the costs of organising and the slower these costs rise with an increase in the number of transactions organised

- the less likely the entrepreneur is to make mistakes and the smaller the increase in mistakes with an increase in the transactions organised

- the greater the lowering (or the smaller the rise) in the supply price of factors of production to firms of larger size

The first two costs will increase with the spatial distribution of the transactions organised and the dissimilarity of the transactions. This explains why firms tend to either be in different geographic locations or to perform different functions. Additionally, technology changes that mitigate the cost of organising transactions across space may allow firms to become larger – the advent of the telephone and of cheap air travel, for example, would be expected to increase the size of firms.

Coase argued that without transaction costs the initial assignment of property rights makes no difference to whether or not the farmer and rancher can achieve the economically efficient outcome. If the cost of restraining cattle by, say, building a fence, is less than the cost of crop damage, the fence will be built. The initial assignment of property rights determines who builds the fence. If the farmer is responsible for the crop damage, the farmer will pay for the fence (as long the fence costs less than the crop damage). If the rancher is responsible for the crop damage, the rancher will build the fence. The allocation of property rights is primarily an equity issue, with consequences for the distribution of income and wealth, rather than an efficiency issue.

With sufficient transaction costs, initial property rights matter for both equity and efficiency. From the point of view of economic efficiency, property rights should be assigned such that the owner of the rights wants to take the economically efficient action. To elaborate, if it is efficient not to restrict the cattle, the rancher should be given the rights (so that cattle can move about freely), whereas if it is efficient to restrict the cattle, the farmer should be given the rights over the movement of the cattle (so the cattle are restricted).

This seminal argument forms the basis of the famous Coase theorem as labelled by Stigler.

Source: Wikipedia

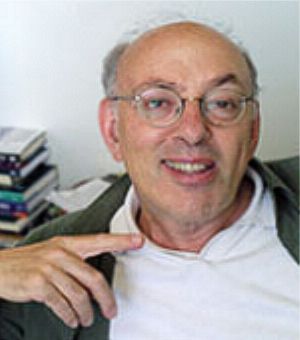

The Derman balcony – named after Professor Emanuel Derman

Emanuel Derman (born c. 1945) is a Jewish South African-born academic, businessman and writer. He is best known as a quantitative analyst, and author of the book My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance.

Emanuel Derman (born c. 1945) is a Jewish South African-born academic, businessman and writer. He is best known as a quantitative analyst, and author of the book My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance.

He is a co-author of Black–Derman–Toy model, one of the first interest-rate models, and the Derman–Kani local volatility or implied tree model, a model consistent with the volatility smile.

Derman, who first came to the U.S. at age 21, in 1966, is currently a professor at Columbia University In 2011, he published “Models.Behaving.Badly,” a book contrasting financial models with the theories of hard science, and also containing some autobiographical material.

Derman was named the IAFE/SunGard Financial Engineer of the Year 2000, and was elected to the Risk Hall of Fame in 2002. He is the author of numerous articles on quantitative finance on the topics of volatility and the nature of financial modeling.

Since 1995, Derman has written many articles pointing out the essential difference between models in physics and models in finance. Good models in physics aim to predict the future accurately from the present, or to predict new previously unobserved phenomena; models in finance are used mostly to estimate the values of illiquid securities from liquid ones. Models in physics deal with objective variables; models in finance deal with subjective ones. “In physics there may one day be a Theory of Everything; in finance and the social sciences, you’re lucky if there is a usable theory of anything.”

Derman together with Paul Wilmott wrote the Financial Modelers’ Manifesto, a set of principles for doing responsible financial modeling.

The Drucker library – named after Professor Peter Drucker

Peter Ferdinand Drucker (November 19, 1909 – November 11, 2005) was an Austrian-born American management consultant, educator, and author, whose writings contributed to the philosophical and practical foundations of the modern business corporation. He was also a leader in the development of management education, he invented the concept known as management by objectives and self-control, and he has been described as “the founder of modern management”. Drucker’s books and scholarly and popular articles explored how humans are organized across the business, government, and nonprofit sectors of society. He is one of the best-known and most widely influential thinkers and writers on the subject of management theory and practice. His writings have predicted many of the major developments of the late twentieth century, including privatization and decentralization; the rise of Japan to economic world power; the decisive importance of marketing; and the emergence of the information society with its necessity of lifelong learning.[4] In 1959, Drucker coined the term “knowledge worker,” and later in his life considered knowledge-worker productivity to be the next frontier of management.

Drucker is considered the single most important thought leader in the world of management, and several ideas run through most of his writings:

- Decentralization and simplification. Drucker discounted the command and control model and asserted that companies work best when they are decentralized. According to Drucker, corporations tend to produce too many products, hire employees they don’t need (when a better solution would be outsourcing), and expand into economic sectors that they should avoid.

- The concept of “knowledge worker” in his 1959 book The Landmarks of Tomorrow. Since then, knowledge-based work has become increasingly important in businesses worldwide.

- The prediction of the death of the “Blue Collar” worker. The changing face of the US Auto Industry is a testimony to this prediction.

- The concept of what eventually came to be known as “outsourcing.” He used the example of “front room” and “back room” of each business: A company should be engaged in only the front room activities that are critical to supporting its core business. Back room activities should be handed over to other companies, for whom these tasks are the front room activities.

- The importance of the non-profit sector, which he calls the third sector (private sector and the Government sector being the first two). Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) play crucial roles in the economies of countries around the world.

- A profound skepticism of macroeconomic theory. Drucker contended that economists of all schools fail to explain significant aspects of modern economies.

- A lament that the sole focus of microeconomics is price, citing its lack of showing what products actually do for us,

- Respect for the worker. Drucker believed that employees are assets not liabilities. He taught that knowledgeable workers are the essential ingredients of the modern economy, and that a hybrid management model is the sole method of demonstrating an employee’s value to the organization. Central to this philosophy is the view that people are an organization’s most valuable resource, and that a manager’s job is both to prepare people to perform and give them freedom to do so.

- A belief in what he called “the sickness of government.” Drucker made nonpartisan claims that government is often unable or unwilling to provide new services that people need and/or want, though he believed that this condition is not intrinsic to the form of government. The chapter “The Sickness of Government” a theory of public administration that dominated the discipline in the 1980s and 1990s.

- The need for “planned abandonment.” Businesses and governments have a natural human tendency to cling to “yesterday’s successes” rather than seeing when they are no longer useful.

- A belief that taking action without thinking is the cause of every failure.

- The need for community. Early in his career, Drucker predicted the “end of economic man” and advocated the creation of a “plant community”

- The need to manage business by balancing a variety of needs and goals, rather than subordinating an institution to a single value.

- A company’s primary responsibility is to serve its customers. Profit is not the primary goal, but rather an essential condition for the company’s continued existence and sustainability.

- A belief in the notion that great companies could stand among humankind’s noblest inventions.

- “Do what you do best and outsource the rest” is a business tagline first “coined and developed”

Source: Wikipedia

The Kahneman meeting room – named after Professor Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman (born March 5, 1934) is an Israeli-American psychologist notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making, as well as behavioral economics, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (shared with Vernon L. Smith). His empirical findings challenge the assumption of human rationality prevailing in modern economic theory.

Daniel Kahneman (born March 5, 1934) is an Israeli-American psychologist notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making, as well as behavioral economics, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (shared with Vernon L. Smith). His empirical findings challenge the assumption of human rationality prevailing in modern economic theory.

With Amos Tversky and others, Kahneman established a cognitive basis for common human errors that arise from heuristics and biases (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973; Kahneman, Slovic & Tversky, 1982; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), and developed prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Together, Kahneman and Tversky published a series of seminal articles in the general field of judgment and decision-making, culminating in the publication of their prospect theory in 1979 (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Kahneman was ultimately awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2002 for his work on prospect theory. Following this, the pair teamed with Paul Slovic to edit a compilation entitled “Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” (1982) which was published in the prestigious journal Science and introduced the notion of anchoring. This proved to be an important summary of their work and of other recent advances that had influenced their thinking.

With David Schkade, Kahneman developed the notion of the focusing illusion (Kahneman & Schkade, 1998; Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz & Stone, 2006) to explain in part the mistakes people make when estimating the effects of different scenarios on their future happiness (also known as affective forecasting, which has been studied extensively by Daniel Gilbert). The “illusion” occurs when people consider the impact of one specific factor on their overall happiness, they tend to greatly exaggerate the importance of that factor, while overlooking the numerous other factors that would in most cases have a greater impact. A good example is provided by Kahneman and Schkade’s 1998 paper “Does living in California make people happy? A focusing illusion in judgments of life satisfaction”. In that paper, students in the Midwest and in California reported similar levels of life satisfaction, but the Midwesterners thought their Californian peers would be happier. The only distinguishing information the Midwestern students had when making these judgments was the fact that their hypothetical peers lived in California. Thus, they “focused” on this distinction, thereby overestimating the effect of the weather in California on its residents’ satisfaction with life.

In 2011, he was named by Foreign Policy magazine to its list of top global thinkers.

He is professor emeritus of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University‘s Woodrow Wilson School. Kahneman is a founding partner of TGG Group, a business and philanthropy consulting company. He is married to Royal Society Fellow Anne Treisman.

In 2015 The Economist listed him as the seventh most influential economist in the world.

Source: Wikipedia

The Kotter touch-down room – named after Dr John Kotter

Dr. John Paul Kotter is the Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership, Emeritus, at the Harvard Business School,

Dr. John Paul Kotter is the Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership, Emeritus, at the Harvard Business School,

Kotter is the author of 20 books, 12 of which have been business bestsellers and two of which are overall New York Times bestsellers.

His international bestseller Leading Change (1996), “is considered by many to be the seminal work in the field of change management.” The book outlines a practical 8-step process for change management :

- Establishing a Sense of Urgency

- Creating the Guiding Coalition

- Developing a Vision and Strategy

- Communicating the Change Vision

- Empowering Employees for Broad-Based Action

- Generating Short-Term Wins

- Consolidating Gains and Producing More Change

- Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture

In 2011, TIME magazine listed Leading Change as one of the “Top 25 Most Influential Business Management Books” of all time.

Our Iceberg is Melting

In 2006, Kotter co-wrote Our Iceberg is Melting with Holger Rathgeber where those same 8 steps were expanded into an allegory about penguins. In the book, a group of penguins whose iceberg is melting must change in order to survive while their iceberg home melts.

Accelerate

More recently, Kotter released Buy In

His educational articles in the Harvard Business Review magazine continue to be among the magazine’s top sellers.

Source: Wikipedia

The Mandelbrot balcony – named after Professor Benoit Mandelbrot

Benoit B.Mandelbrot found that price changes in financial markets did not follow a Gaussian distribution, but rather Lévy stable distributions having theoretically infinite variance. He found, for example, that cotton prices followed a Lévy stable distribution with parameter ? equal to 1.7 rather than 2 as in a Gaussian distribution. “Stable” distributions have the property that the sum of many instances of a random variable follows the same distribution but with a larger scale parameter.

Benoit B.Mandelbrot found that price changes in financial markets did not follow a Gaussian distribution, but rather Lévy stable distributions having theoretically infinite variance. He found, for example, that cotton prices followed a Lévy stable distribution with parameter ? equal to 1.7 rather than 2 as in a Gaussian distribution. “Stable” distributions have the property that the sum of many instances of a random variable follows the same distribution but with a larger scale parameter.

As a visiting professor at Harvard University, Mandelbrot began to study fractals called Julia sets that were invariant under certain transformations of the complex plane. Building on previous work by Gaston Julia and Pierre Fatou, Mandelbrot used a computer to plot images of the Julia sets. While investigating the topology of these Julia sets, he studied the Mandelbrot set fractal that is now named after him. In 1982, Mandelbrot expanded and updated his ideas in The Fractal Geometry of Nature. This influential work brought fractals into the mainstream of professional and popular mathematics, as well as silencing critics, who had dismissed fractals as “program artifacts“.

Mandelbrot ended up doing a great piece of science and identifying a much stronger and more fundamental idea—put simply, that there are some geometric shapes, which he called “fractals”, that are equally “rough” at all scales. No matter how close you look, they never get simpler, much as the section of a rocky coastline you can see at your feet looks just as jagged as the stretch you can see from space.

According to Arthur C. Clarke, “the Mandelbrot set is indeed one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics. Who could have dreamed that such an incredibly simple equation could have generated images of literally infinite complexity?” Clarke also notes an “odd coincidence:” “the name Mandelbrot, and the word “mandala“—for a religious symbol—which I’m sure is a pure coincidence, but indeed the Mandelbrot set does seem to contain an enormous number of mandalas.”

Source: Wikipedia

The Markowitz boardroom – named after Professor Harry Markowitz

Harry Max Markowitz (born August 24, 1927) is an American economist, and a recipient of the 1989 John von Neumann Theory Prize and the 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Harry Max Markowitz (born August 24, 1927) is an American economist, and a recipient of the 1989 John von Neumann Theory Prize and the 1990 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Markowitz is a professor of finance at the Rady School of Management at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). He is best known for his pioneering work in modern portfolio theory, studying the effects of asset risk, return, correlation and diversification on probable investment portfolio returns. With George Dantzig’s help, Markowitz continued to research optimization techniques, further developing the critical line algorithm for the identification of the optimal mean-variance portfolios, relying on what was later named the Markowitz frontier.

Harry Markowitz put forward this model in 1952. It assists in the selection of the most efficient by analyzing various possible portfolios of the given securities. By choosing securities that do not ‘move’ exactly together, the HM model shows investors how to reduce their risk. The HM model is also called mean–variance model due to the fact that it is based on expected returns (mean) and the standard deviation (variance) of the various portfolios.

A Markowitz-efficient portfolio is one where no added diversification can lower the portfolio’s risk for a given return expectation (alternately, no additional expected return can be gained without increasing the risk of the portfolio). The Markowitz Efficient Frontier is the set of all portfolios that will give the highest expected return for each given level of risk. These concepts of efficiency were essential to the development of the capital asset pricing model.

Source: Wikipedia

The Mintzberg meeting room – named after Professor Henry Mintzberg

Henry Mintzberg, OC OQ FRSC (born September 2, 1939) is an internationally renowned academic and author on business and management. He is currently the Cleghorn Professor of Management Studies at the Desautels Faculty of Management of McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, where he has been teaching since 1968.

Henry Mintzberg, OC OQ FRSC (born September 2, 1939) is an internationally renowned academic and author on business and management. He is currently the Cleghorn Professor of Management Studies at the Desautels Faculty of Management of McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, where he has been teaching since 1968.

Henry Mintzberg writes prolifically on the topics of management and business strategy, with more than 150 articles and fifteen books to his name. His seminal book, The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (Mintzberg 1994), criticizes some of the practices of strategic planning today.

In 2004 he published a book entitled Managers Not MBAs (Mintzberg 2004) which outlines what he believes to be wrong with management education today. Mintzberg claims that prestigious graduate management schools like Harvard Business School and the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania are obsessed with numbers and that their overzealous attempts to make management a science are damaging the discipline of management. Mintzberg advocates more emphasis on post graduate programs that educate practicing managers (rather than students with little real world experience) by relying upon action learning and insights from their own problems and experiences.

The organizational configurations framework of Mintzberg is a model that describes six valid organizational configurations (originally only five; the sixth one was added later):

- Simple structure characteristic of entrepreneurial organization

- Machine bureaucracy

- Professional bureaucracy

- Diversified form

- Adhocracy or Innovative organization

Regarding the coordination between different tasks, Mintzberg defines the following mechanisms:

- Mutual adjustment, which achieves coordination by the simple process of informal communication (as between two operating employees)

- Direct supervision, is achieved by having one person issue orders or instructions to several others whose work interrelates (as when a boss tells others what is to be done, one step at a time)

- Standardization of work processes, which achieves coordination by specifying the work processes of people carrying out interrelated tasks (those standards usually being developed in the technostructure to be carried out in the operating core, as in the case of the work instructions that come out of time-and-motion studies)

- Standardization of outputs, which achieves coordination by specifying the results of different work (again usually developed in the technostructure, as in a financial plan that specifies subunit performance targets or specifications that outline the dimensions of a product to be produced)

- Standardization of skills (as well as knowledge), in which different work is coordinated by virtue of the related training the workers have received (as in medical specialists – say a surgeon and an anesthetist in an operating room –responding almost automatically to each other’s standardized procedures)

- Standardization of norms, in which it is the norms infusing the work that are controlled, usually for the entire organization, so that everyone functions according to the same set of beliefs (as in a religious order)

According to the organizational configurations model of Mintzberg, each organization can consist of a maximum of six basic parts:

- Strategic Apex (top management)

- Middle Line (middle management)

- Operating Core (operations, operational processes)

- Technostructure (analysts that design systems, processes, etc.)

- Support Staff (support outside of operating workflow)

- Ideology (halo of beliefs and traditions; norms, values, culture)

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Mintzberg’s research findings and writing on business strategy, is that they have often emphasized the importance of emergent strategy, which arises informally at any level in an organisation, as an alternative or a complement to deliberate strategy, which is determined consciously either by top management or with the acquiescence of top management.

Mintzberg is cited in Chamberlain’s Theory of Strategy as providing one of the four main foundations on which the theory is based.

Source: Wikipedia

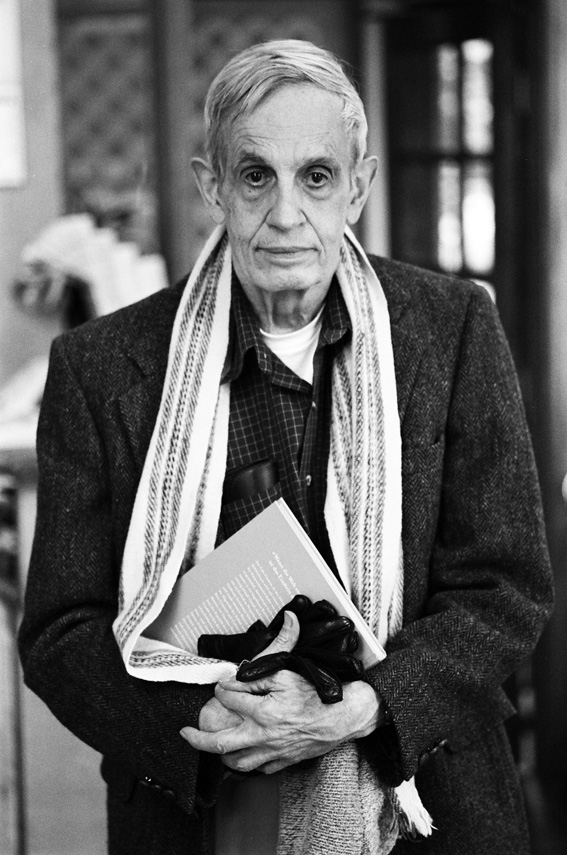

The Nash balcony – named after Dr John Nash

John Forbes Nash Jr. (June 13, 1928 – May 23, 2015) was an American mathematician who made fundamental contributions to game theory, differential geometry, and the study of partial differential equations. Nash’s work has provided insight into the factors that govern chance and decision-making inside complex systems found in everyday life.

John Forbes Nash Jr. (June 13, 1928 – May 23, 2015) was an American mathematician who made fundamental contributions to game theory, differential geometry, and the study of partial differential equations. Nash’s work has provided insight into the factors that govern chance and decision-making inside complex systems found in everyday life.

His theories are widely used in economics. Serving as a Senior Research Mathematician at Princeton University during the latter part of his life, he shared the 1994 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with game theorists Reinhard Selten and John Harsanyi. In 2015, he also shared the Abel Prize with Louis Nirenberg for his work on nonlinear partial differential equations.

Nash earned a Ph.D. degree in 1950 with a 28-page dissertation on non-cooperative games. The thesis, which was written under the supervision of doctoral advisor Albert W. Tucker, contained the definition and properties of the Nash equilibrium. A crucial concept in non-cooperative games, it won Nash the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994.

Nash did groundbreaking work in the area of real algebraic geometry.

Source: Wikipedia

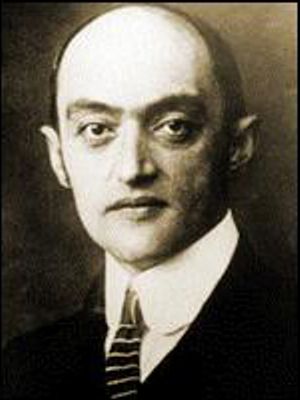

The Schumpeter touch-down room – named after Professor Joseph Schumpeter

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (8 February 1883 – 8 January 1950)

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (8 February 1883 – 8 January 1950)

According to Christopher Freeman (2009), a scholar who devoted much time researching Schumpeter’s work: “the central point of his whole life work [is]: that capitalism can only be understood as an evolutionary process of continuous innovation and ‘creative destruction'”.

Schumpeter’s relationships with the ideas of other economists were quite complex in his most important contributions to economic analysis – the theory of business cycles and development. Following neither Walras nor Keynes, Schumpeter starts in The Theory of Economic Development with a treatise of circular flow which, excluding any innovations and innovative activities, leads to a stationary state. The stationary state is, according to Schumpeter, described by Walrasian equilibrium. The hero of his story is the entrepreneur.

The entrepreneur disturbs this equilibrium and is the prime cause of economic development, which proceeds in cyclic fashion along several time scales. In fashioning this theory connecting innovations, cycles, and development, Schumpeter kept alive the Russian Nikolai Kondratiev’s ideas on 50-year cycles, Kondratiev waves.

Schumpeter suggested a model in which the four main cycles, Kondratiev (54 years), Kuznets (18 years), Juglar (9 years) and Kitchin (about 4 years) can be added together to form a composite waveform. Actually there was considerable professional rivalry between Schumpeter and Kuznets. The wave form suggested here did not include the Kuznets Cycle simply because Schumpeter did not recognize it as a valid cycle. See “business cycle” for further information. A Kondratiev wave could consist of three lower degree Kuznets waves. Each Kuznets wave could, itself, be made up of two Juglar waves. Similarly two (or three) Kitchin waves could form a higher degree Juglar wave. If each of these were in phase, more importantly if the downward arc of each was simultaneous so that the nadir of each was coincident it would explain disastrous slumps and consequent depressions. As far as the segmentation of the Kondratiev Wave, Schumpeter never proposed such a fixed model. He saw these cycles varying in time – although in a tight time frame by coincidence – and for each to serve a specific purpose.

Schumpeter was probably the first scholar to theorize about entrepreneurship, and the field owed much to his contributions. His fundamental theories are often referred to as Mark I and Mark II. In the first, Schumpeter argued that the innovation and technological change of a nation come from the entrepreneurs, or wild spirits. He coined the word Unternehmergeist, German for “entrepreneur-spirit”, and asserted that “… the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way” stemmed directly from the efforts of entrepreneurs.

Schumpeter was the most influential thinker to argue that long cycles are caused by innovation, and are an incident of it. His treatise on business cycles developed were based on Kondratiev’s ideas which attributed the causes very differently. Schumpeter’s treatise brought Kondratiev’s ideas to the attention of English-speaking economists. Kondratiev fused important elements that Schumpeter missed. Yet, the Schumpeterian variant of long-cycles hypothesis, stressing the initiating role of innovations, commands the widest attention today.

The technological view of change needs to demonstrate that changes in the rate of innovation governs changes in the rate of new investments, and that the combined impact of innovation clusters takes the form of fluctuation in aggregate output or employment. The process of technological innovation involves extremely complex relations among a set of key variables: inventions, innovations, diffusion paths and investment activities. The impact of technological innovation on aggregate output is mediated through a succession of relationships that have yet to be explored systematically in the context of long wave. New inventions are typically primitive, their performance is usually poorer than existing technologies and the cost of their production is high. A production technology may not yet exist, as is often the case in major chemical inventions, pharmaceutical inventions. The speed with which inventions are transformed into innovations and diffused depends on actual and expected trajectory of performance improvement and cost reduction.

Schumpeter identified innovation as the critical dimension of economic change.

Source: Wikipedia

The Stiglitz data centre – named after Professor Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (born February 9, 1943) is an American economist and a professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979). He is a former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank and is a former member and chairman of the (US president’s) Council of Economic Advisers. and for his critical view of the management of globalization, of laissez-faire economists (whom he calls “free market fundamentalists“), and of international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (born February 9, 1943) is an American economist and a professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979). He is a former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank and is a former member and chairman of the (US president’s) Council of Economic Advisers. and for his critical view of the management of globalization, of laissez-faire economists (whom he calls “free market fundamentalists“), and of international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

In 2000, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), a think tank on international development based at Columbia University. He has been a member of the Columbia faculty since 2001, and received that university’s highest academic rank (university professor) in 2003. He was the founding chair of the university’s Committee on Global Thought. He also chairs the University of Manchester‘s Brooks World Poverty Institute. He is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. In 2009, the President of the United Nations General Assembly Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, appointed Stiglitz as the chairman of the U.N. Commission on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System, where he oversaw suggested proposals and commissioned a report on reforming the international monetary and financial system.

Stiglitz has received more than 40 honorary degrees, including from Harvard, Oxford, and Cambridge Universities and been decorated by several governments including Korea, Colombia, Ecuador, and most recently France, where he was appointed a member of the Legion of Honor, order Officer.

Based on academic citations, Stiglitz is the 4th most influential economist in the world today,

Stiglitz made early contributions to a theory of public finance stating that an optimal supply of local public goods can be funded entirely through capture of the land rents generated by those goods (when population distributions are optimal). Stiglitz dubbed this the ‘Henry George theorem‘ in reference to the radical classical economistHenry George who famously advocated for land value tax. The explanation behind Stiglitz’s finding is that rivalry for public goods takes place geographically, so competition for access to any beneficial public good will increase land values by at least as much as its outlay cost. Furthermore, Stiglitz shows that a single tax on rents is necessary to provide the optimal supply of local public investment. Stiglitz also shows how the theorem could be used to find the optimal size of a city or firm.

Stiglitz’s most famous research was on screening, a technique used by one economic agent to extract otherwise private information from another. It was for this contribution to the theory of information asymmetry that he shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2001 “for laying the foundations for the theory of markets with asymmetric information” with George A. Akerlof and A. Michael Spence.

Before the advent of models of imperfect and asymmetric information, the traditional neoclassical economics literature had assumed that markets are efficient except for some limited and well defined market failures. More recent work by Stiglitz and others reversed that presumption, to assert that it is only under exceptional circumstances that markets are efficient. Stiglitz has shown (together with Bruce Greenwald) that “whenever markets are incomplete and/or information is imperfect (which are true in virtually all economies), even competitive market allocation is not constrained Pareto efficient“. In other words, they addressed “the problem of determining when tax interventions are Pareto-improving. The approach indicates that such tax interventions almost always exist and that equilibria in situations of imperfect information are rarely constrained Pareto optima.”

Stiglitz also did research on efficiency wages, and helped create what became known as the “Shapiro-Stiglitz model” to explain why there is unemployment even in equilibrium, why wages are not bid down sufficiently by job seekers (in the absence of minimum wages) so that everyone who wants a job finds one, and to question whether the neoclassical paradigm could explain involuntary unemployment. Two basic observations undergird their analysis:

- Unlike other forms of capital, humans can choose their level of effort.

- It is costly for firms to determine how much effort workers are exerting.

In addition to being awarded the Nobel Memorial prize, Stiglitz has over 40 honorary doctorates and at least eight honorary professorships, as well as an honorary deanship.

In 2011, he was named by Foreign Policy magazine on its list of top global thinkers.

Source: Wikipedia

The Von Neumann consultants’ work area – named after Professor John von Neumann

John von Neumann (December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, inventor, computer scientist, and polymath. He made major contributions to a number of fields, including mathematics (foundations of mathematics, functional analysis, ergodic theory, geometry, topology, and numerical analysis), physics (quantum mechanics, hydrodynamics, and quantum statistical mechanics), economics (game theory), computing (Von Neumann architecture, linear programming, self-replicating machines, stochastic computing), and statistics.

John von Neumann (December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, inventor, computer scientist, and polymath. He made major contributions to a number of fields, including mathematics (foundations of mathematics, functional analysis, ergodic theory, geometry, topology, and numerical analysis), physics (quantum mechanics, hydrodynamics, and quantum statistical mechanics), economics (game theory), computing (Von Neumann architecture, linear programming, self-replicating machines, stochastic computing), and statistics.

He was a pioneer of the application of operator theory to quantum mechanics, in the development of functional analysis, and a key figure in the development of game theory and the concepts of cellular automata, the universal constructor and the digital computer. He published over 150 papers in his life: about 60 in pure mathematics, 20 in physics, and 60 in applied mathematics, the remainder being on special mathematical subjects or non-mathematical ones. His last work, an unfinished manuscript written while in the hospital, was later published in book form as The Computer and the Brain.

His analysis of the structure of self-replication preceded the discovery of the structure of DNA. In a short list of facts about his life he submitted to the National Academy of Sciences, he stated “The part of my work I consider most essential is that on quantum mechanics, which developed in Göttingen in 1926, and subsequently in Berlin in 1927–1929. Also, my work on various forms of operator theory, Berlin 1930 and Princeton 1935–1939; on the ergodic theorem, Princeton, 1931–1932.”

The Nobel Laureate Hans Bethe speculated: “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man”.

During World War II he worked on the Manhattan Project, developing the mathematical models behind the explosive lenses used in the implosion-type nuclear weapon. After the war, he served on the General Advisory Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, and later as one of its commissioners. He was a consultant to a number of organizations, including the United States Air Force, the Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Along with theoretical physicist Edward Teller, mathematician Stanislaw Ulam, and others, he worked out key steps in the nuclear physics involved in thermonuclear reactions and the hydrogen bomb.

Stan Ulam, who knew von Neumann well, described his mastery of mathematics this way: “Most mathematicians know one method. For example, Norbert Wiener had mastered Fourier transforms. Some mathematicians have mastered two methods and might really impress someone who knows only one of them. John von Neumann had mastered three methods.” He went on to explain that the three methods were:

- A facility with the symbolic manipulation of linear operators;

- An intuitive feeling for the logical structure of any new mathematical theory;

- An intuitive feeling for the combinatorial superstructure of new theories.

Edward Teller wrote that “Nobody knows all science, not even von Neumann did. But as for mathematics, he contributed to every part of it except number theory and topology. That is, I think, something unique.”

Von Neumann was asked to write an essay for the layman describing what mathematics is, and produced a beautiful analysis. He explained that mathematics straddles the world between the empirical and logical, arguing that geometry was originally empirical, but Euclid constructed a logical, deductive theory. However, he argued, that there is always the danger of straying too far from the real world and becoming irrelevant sophistry.

Von Neumann was a founding figure in computing.

Von Neumann’s hydrogen bomb work was played out in the realm of computing, where he and Stanislaw Ulam developed simulations on von Neumann’s digital computers for the hydrodynamic computations. During this time he contributed to the development of the Monte Carlo method, which allowed solutions to complicated problems to be approximated using random numbers.

Stochastic computing was first introduced in a pioneering paper by von Neumann in 1953.

“It seems fair to say that if the influence of a scientist is interpreted broadly enough to include impact on fields beyond science proper, then John von Neumann was probably the most influential mathematician who ever lived,” wrote Miklós Rédei in “Selected Letters.” James Glimm wrote: “he is regarded as one of the giants of modern mathematics”.

Source: Wikipedia

The new offices in central Sandton

Our previous Hyde Park offices

The new offices – Planning and construction

The new offices – Post completion